What We Review

The Defeat of Reconstruction: Understanding How Reconstruction Ended

Reconstruction was a pivotal period in American history, lasting from 1865 to 1877. It was the time right after the Civil War when the federal government sought to rebuild the South and ensure newly freed African Americans had a secure place in society. However, by the late 1870s, progress began to unwind. This post explores how did Reconstruction end and why it remains significant today.

The Context of Reconstruction

Reconstruction had several main goals:

- Restore the nation by reuniting North and South.

- Address the major inequalities left by slavery.

- Integrate freed African Americans into society with equal rights.

In its early stages, Reconstruction saw success. The federal government established amendments to the Constitution, including the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. These laws abolished slavery, provided citizenship rights, and protected voting rights. For a brief moment, African Americans served in political offices, setting a powerful precedent for future generations.

However, tensions between the North and the South continued. Despite the added legal protections, some white Southerners resisted federal authority. As a result, Reconstruction’s reforms faced growing challenges in the late 1870s.

The Election of 1876 and the Compromise of 1877

A Tumultuous Election

The 1876 presidential race between Rutherford B. Hayes (Republican) and Samuel J. Tilden (Democrat) was extremely controversial. Tilden won the popular vote, but the electoral votes in three Southern states were in dispute. This uncertainty threatened to plunge the nation into more turmoil.

The Compromise of 1877 Definition

To resolve the crisis, the Compromise of 1877 was formed. Under this agreement:

- Congress allowed Rutherford B. Hayes to become president.

- Federal troops would leave the remaining Southern states.

- Funding would be provided for railroad projects in the South.

Why It Mattered

Federal troops had been protecting African Americans and Republican governments in the South. Once these troops withdrew, local white leaders gained more freedom to enforce discriminatory laws. Therefore, the compromise ended the direct federal support for Reconstruction efforts. Step by step, Southern states began rolling back laws that protected African Americans. This shift helped end the era of Reconstruction and set the stage for decades of harsh Jim Crow policies.

The Rise of Segregation Laws

When the federal government reduced its presence, some Southern states began writing new constitutions. These constitutions enabled more explicit de jure segregation laws, which legally separated people based on their race. Commonly called “Jim Crow” laws, these rules touched every aspect of daily life.

From Social to Legal Division

- Public spaces such as schools and transportation were divided by race.

- Marriage between Black and white citizens was banned in many states.

- Businesses could legally refuse service to Black patrons.

Louisiana offers a clear example of how segregation worked step by step. The state legislature passed laws that forced African Americans to use separate streetcars and railroad cars. Over time, these laws expanded to include restaurants, theaters, and other public places. As federal oversight diminished, these segregation measures rapidly spread throughout the South.

Suppression of Black Voting

Even though the 15th Amendment protected voting rights, some Southern leaders designed ways to stop Black citizens from casting ballots. Methods included:

- Poll taxes: Voters had to pay a fee to vote, which many Black farmers could not afford.

- Literacy tests: Voters had to pass a reading and writing exam. This test was often unjustly administered, targeting African Americans with more difficult questions.

- Grandfather clauses: Those whose ancestors voted before 1867 could bypass tests and taxes. This obviously benefitted white citizens, since most Black Americans did not have that voting history in their families.

By targeting African Americans’ right to vote, states used the legal system to weaken any remaining political power they had gained during Reconstruction. This meant fewer Black voices influenced government decisions, and racist laws were less likely to face opposition.

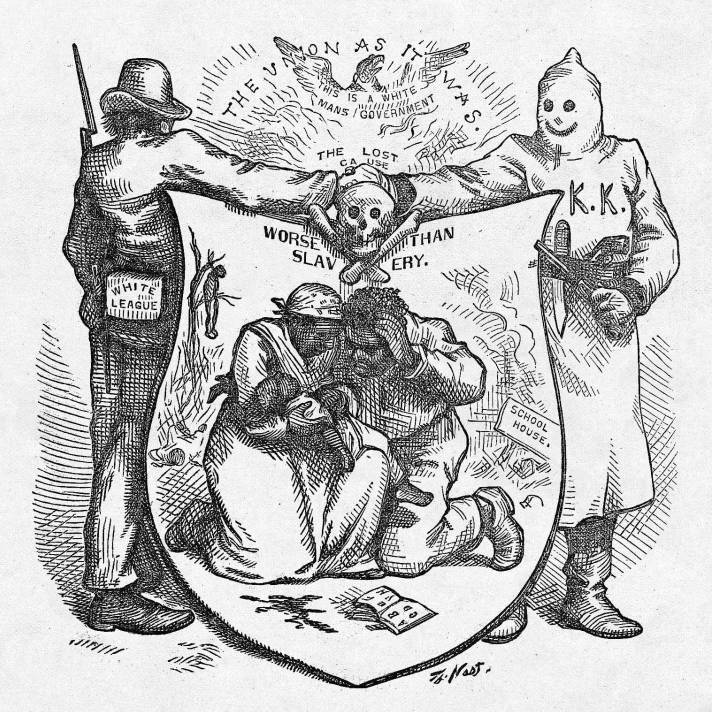

The Role of Racial Violence and the Ku Klux Klan

Legal intimidation was not the only factor in Reconstruction’s defeat. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan also used violence, threats, and harassment to control African Americans. These secret societies emerged soon after the Civil War ended.

Methods of Fear

- Burning homes and churches to send a warning.

- Lynching and physical attacks against Black citizens who tried to vote or speak out.

- Nighttime raids with members wearing hooded robes to hide their identities.

For example, in many rural areas, African Americans who desired to run for public office or promote education faced violent backlash. Over time, such brutality drove many away from political life. The fear spread and weakened the push for equal rights in the South.

Plessy v. Ferguson: The Legalization of Segregation

Plessy and Ferguson: The “Separate but Equal” Case

One major Supreme Court case that reinforced these segregation policies was Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. In this lawsuit, Homer Plessy—a man of mixed race—challenged a Louisiana law requiring separate train cars for Black and white passengers. Specifically, he sat in a “whites-only” car and was arrested. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court.

The Court’s Ruling

The Court ruled that racial segregation did not violate the 14th Amendment. This decision established the doctrine of “separate but equal.” It meant that racially separate facilities would remain constitutional as long as they offered both groups “equal” services. In reality, these facilities were rarely equal. Most Black institutions received less funding and had poorer conditions.

For example, African American schools often had outdated books and limited supplies, while white schools were well-funded. This disparity shaped the lives of many Black Americans for decades. “Separate but equal” remained the law until it was finally challenged in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

The Long-term Effects of the End of Reconstruction

When federal forces left and racist policies spread, the positive gains of Reconstruction began to fade. State and local governments were free to enact:

- Segregation in schools, businesses, and public facilities.

- Heavy voting restrictions on Black citizens.

- Legal acceptance of violent white supremacist groups.

Over time, the idea of equal rights seemed out of reach for many African Americans. Nevertheless, Black communities developed their own institutions, including churches and schools, to maintain resilience. These communities played critical roles in sparking the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century.

Lasting Legacies

Although Reconstruction ended in disappointment, it set the foundation for future struggles for equality. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments remained in the Constitution, providing a legal basis for civil rights campaigns. The legacy of this period reminds Americans that change can be reversed without constant vigilance and federal enforcement.

Conclusion

The end of Reconstruction was not a single event but a process shaped by the Compromise of 1877, new segregation laws, suppressed voting, terror from groups like the Ku Klux Klan, and legal backing in cases such as Plessy v. Ferguson. These developments helped dismantle many advances that African Americans had gained.

Understanding the defeat of Reconstruction is crucial for recognizing the roots of America’s racial injustices. It also shows that laws must be carefully protected and enforced. Learning about this era illuminates why civil rights movements continued well into the 20th century and why these struggles still resonate in American society today.

Required Source: Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court Ruling, 1896

The official text of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision provides insight into how the Supreme Court justified segregation. While Homer Plessy argued that the Louisiana Separate Car Act violated the 14th Amendment, the Court disagreed. It stated that separating races did not necessarily imply one was inferior to the other and that the law did not violate the Constitution. This ruling opened the door for states to create various “separate but equal” facilities that were, in practice, far from equal.

Historically, this ruling paved the way for a nationwide expansion of segregation laws. Its relevance lies in how it gave legal sanction to a system that kept African Americans segregated for decades. This decision directly connects to the broader narrative of Reconstruction’s defeat because it legitimized the racial inequalities that took hold after the Compromise of 1877. Although later overruled by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Plessy v. Ferguson case remains one of the most well-known examples of how institutional racism was supported by the highest court in the land.

Quick Reference: Vocabulary and Key Features

| Term | Definition |

| Reconstruction | The period following the Civil War focused on rebuilding the South and integrating freed slaves. |

| Compromise of 1877 | An agreement that resolved the disputed 1876 presidential election and ended Reconstruction by removing federal troops. |

| De jure segregation | Legal separation of groups in society, often based on race. |

| Poll taxes | Fees required to vote, used to limit access for Black voters. |

| Literacy tests | Requirements that voters prove their reading and writing abilities, often unfairly administered. |

| Grandfather clauses | Laws allowing people to bypass literacy tests or poll taxes if their ancestors had voted before 1867. |

| Ku Klux Klan | A white supremacist group formed to intimidate and control African Americans through violence. |

| Plessy v. Ferguson | A Supreme Court case that upheld segregation laws under the doctrine of “separate but equal.” |

Reconstruction’s defeat was neither quick nor simple: it happened through political deals, voting restrictions, racial violence, and unjust laws. Its lessons underscore the importance of federal enforcement and continuous vigilance for the protection of civil rights. Understanding how these changes occurred helps students appreciate the ongoing struggle for equality in American history.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® African American Studies

Are you preparing for the AP® African American Studies test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® African American Studies problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® African American Studies exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® African American Studies practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.