What We Review

Resistance and Revolts in the United States

Understanding African American resistance and slave revolts is a vital part of grasping the broader struggle against slavery. From small, daily acts to large-scale uprisings, these events shaped the discussion about freedom and citizenship in the United States. They also paved the way for future movements focused on equality and justice. This post explores the different forms of resistance and their significance in African American history.

Daily Forms of Resistance

Daily resistance included quiet, persistent actions that challenged the system of slavery. Enslaved and free African Americans often used tactics such as:

- Slowing down their work

- Breaking or misplacing tools

- Stealing food to supplement scarce rations

- Attempting to run away

These everyday strategies helped maintain a sense of dignity and autonomy. They also forced enslavers to pay attention to the desires of the people they tried to control.

An Example of Resistance

Imagine an enslaved person named William rising before sunrise. He starts his day by working more slowly than usual, pretending to be tired. Later, he carefully loosens the handle on a hoe so it breaks when used at full force. While everyone stops to replace the tool, William takes the chance to share news of an upcoming secret church service. These subtle acts do not overthrow slavery in a single day. However, they quietly chip away at a system that depended on forced labor, helping sustain the larger momentum toward abolition.

Inspirational Figures and Key Revolts

Beyond daily resistance, enslaved people sometimes launched organized uprisings to fight for freedom. Several leaders became symbols of courage and determination, inspiring others to take action.

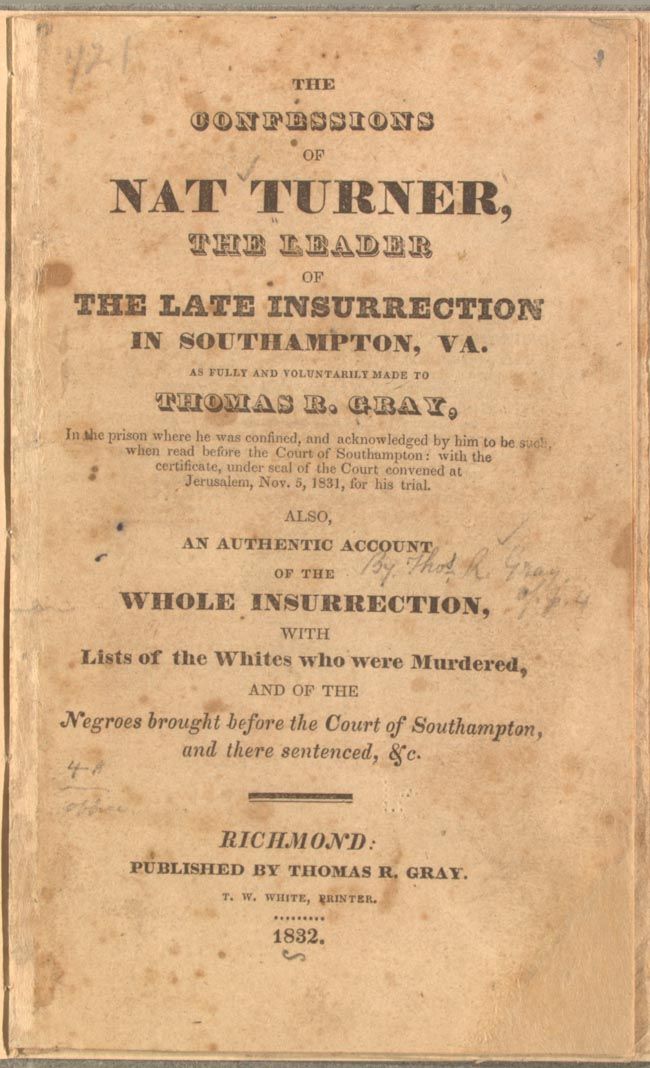

Nat Turner’s Rebellion

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, also known as Nat Turner’s Revolt, began in August 1831 in Virginia. Turner, a deeply religious man, felt called to fight against the injustice of slavery. He and his followers used stealth and surprise to challenge local authorities. Although the revolt was eventually suppressed, it caused widespread alarm among enslavers and led to harsher laws. At the same time, it sparked new energy within the abolition movement, drawing attention to the moral and social crisis of slavery.

Charles Deslondes, German Coast Uprising, and Maroon Communities

In 1811, Charles Deslondes, a formerly enslaved man of Haitian descent, led what is now known as the German Coast Uprising or the Louisiana Revolt—one of the largest slave revolts in U.S. history. The revolt occurred along the Mississippi River just outside of New Orleans, an area densely populated with sugar plantations and known as the “German Coast” due to its early European settlers. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), which had successfully overthrown French colonial rule and ended slavery in Haiti, Deslondes and an estimated 200 to 500 enslaved people organized an armed rebellion. Armed with tools, makeshift weapons, and a powerful vision of freedom, they began a march toward New Orleans, hoping to seize the city, dismantle the plantation system, and establish a more just social order.

Although the group was ultimately stopped by a combination of local militias, U.S. Army troops, and plantation owners, their attempt reflected the far-reaching influence of revolutionary ideals and the willingness of enslaved people to risk everything in pursuit of freedom.

Maroon communities—settlements established by self-liberated Africans and African Americans—played a vital role in the development, planning, and communication surrounding the 1811 uprising. These communities often served as safe havens and information networks, especially in Louisiana’s swampy terrain where surveillance was difficult. Many maroons in the region were formerly enslaved people from Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) who had fled the Haitian Revolution or arrived with refugee populations. They brought with them firsthand knowledge of successful resistance strategies and contributed revolutionary ideas to the enslaved populations of Louisiana.

Although the German Coast Uprising was violently suppressed—many rebels were killed in battle or executed afterward—it marked a significant act of organized resistance. The insurrection challenged the narrative that enslaved people were passive or powerless, showing instead how collective action, cultural memory, and transatlantic solidarity could fuel efforts to fight oppression. The revolt also served as a warning to white authorities, who responded by tightening slave codes and increasing surveillance—further illustrating the fear inspired by Black resistance and the threat it posed to the institution of slavery.

Madison Washington and the Creole Revolt

Madison Washington led a different kind of revolt in 1841, yet it also demonstrated remarkable bravery. While working as an enslaved cook aboard the slave ship Creole, which was transporting people from Virginia to New Orleans, Washington seized control of the vessel. With help from others, he sailed it to the Bahamas, a territory under British rule that had ended slavery in 1833. As a result of this mutiny, nearly 130 enslaved people gained their freedom, proving that resistance could succeed even at sea.

The Role of Religion in Resistance

Religion often served as a unifying force for enslaved and free African Americans. Churches provided safe places to gather, share information, and plan. Religious communities also offered moral support, speaking of freedom and hope. Preachers turned their sermons into rallying cries, mentioning Biblical themes of liberation and justice.

Religious Leaders and Abolition

Enslaved and free Black religious figures like Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Maria W. Stewart, and Henry Highland Garnet channeled their faith into powerful activism. Their sermons or speeches urged listeners to see slavery as a grave moral sin. Therefore, many worship spaces functioned as hubs for both spiritual nourishment and political organizing.

In the North, religious institutions frequently hosted abolitionist meetings, giving the movement a firm base for expansion. These efforts reinforced messages of equality and spurred people to volunteer, donate, or otherwise help the fight against slavery.

The Legacy of Resistance

Resistance, both small and large, made a lasting impression on history. Daily acts of defiance showed that enslaved people never passively accepted their situation. They challenged the system and demanded recognition as human beings. Meanwhile, pivotal revolts like Nat Turner’s Rebellion and the German Coast Uprising inspired abolitionists to intensify their efforts.

Over time, these struggles inflamed public debate. Some communities tightened laws to prevent further uprisings, yet outrage over these crackdowns fueled greater support for ending slavery. By the mid-19th century, newspapers, pamphlets, and public speakers ensured these stories reached a wide audience. As a result, these combined acts of resistance helped shape discussions about human rights, forming a pathway for the Civil War and the eventual abolition of slavery in 1865.

Required Source: Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Rufus King, 1802

To understand the political climate surrounding these revolutions and daily acts of resistance, it is helpful to examine primary documents like Thomas Jefferson’s letter to Rufus King from 1802. In this letter, Jefferson discussed concerns about the spread of revolutions, especially after the Haitian Revolution. He worried that the success of formerly enslaved people in Haiti could inspire others in the United States.

Historical Context and Relevance

- The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) demonstrated that enslaved populations could effectively overthrow powerful colonial forces.

- U.S. leaders, including Thomas Jefferson, feared that such uprisings would reach American soil and disrupt the nation’s economy, which depended on enslaved labor.

- Jefferson’s letter shows how influential policy makers kept a watchful eye on events in the Caribbean, knowing these revolts could spur similar rebellions at home.

Connection to the Topic

This correspondence helps explain why uprisings like the German Coast Uprising alarmed authorities. It shows that the ideas of liberty and independence crossed borders and that leaders were uneasy about the powerful message these revolts sent to all enslaved communities. Understanding this letter enriches the study of resistance, indicating that concerns over rebellion were not just local but spanned international discussions and political debates.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a quick reference chart that highlights key terms and figures related to resistance and revolts in the United States. Feel free to copy and paste this table into a Google Doc:

| Term/Name | Definition or Key Feature |

| Daily Resistance | Small acts such as slowing work, breaking tools, or stealing food |

| Maroon Communities | Groups formed by those who escaped slavery and lived in remote areas |

| Nat Turner’s Rebellion | 1831 uprising led by Nat Turner in Virginia, notable for its religious inspiration |

| Charles Deslondes | Leader of the 1811 German Coast Uprising, influenced by the Haitian Revolution |

| German Coast Uprising | Also known as the Louisiana Revolt of 1811, involved up to 500 enslaved people |

| Madison Washington | Led the 1841 Creole Revolt aboard a slave ship, resulting in 130 people gaining freedom |

| Religious Resistance | Church-based support and planning, including sermons and secret gatherings |

| Thomas Jefferson’s Letter to Rufus King (1802) | Document reflecting fears of spreading revolutions after Haiti’s success |

Conclusion

Resistance and revolts formed a crucial part of African American history. Daily tactics maintained morale and demonstrated the unbreakable will of enslaved people. Larger revolts, though often met with harsh retaliation, sent shockwaves through the nation, forcing debates about human rights and freedom. Together, these efforts helped build the foundation for the eventual abolition of slavery and continued struggles for civil rights.

Studying these acts of resistance reveals a rich tapestry of bravery and persistence. These stories encourage deeper analysis of the broader forces shaping the United States. They also show that even under oppressive conditions, the human spirit found ways to challenge injustice.

Further Resources

- “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” by Harriet Jacobs – A personal account of enslaved life and resistance.

- “The Confessions of Nat Turner” (Original Document) – Primary source on Nat Turner’s mindset and motivations.

- “From Slavery to Freedom” by John Hope Franklin and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham – Comprehensive survey of African American history.

- Local archives and PBS documentaries on regional revolts and maroon communities for further insight.

These resources enhance the understanding of African American resistance, helping students explore beyond a textbook overview. They provide personal narratives, scholarly analysis, and local perspectives, enabling a well-rounded grasp of critical events.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® African American Studies

Are you preparing for the AP® African American Studies test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® African American Studies problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® African American Studies exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® African American Studies practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.