What We Review

African Resistance on Slave Ships and the Antislavery Movement

Introduction

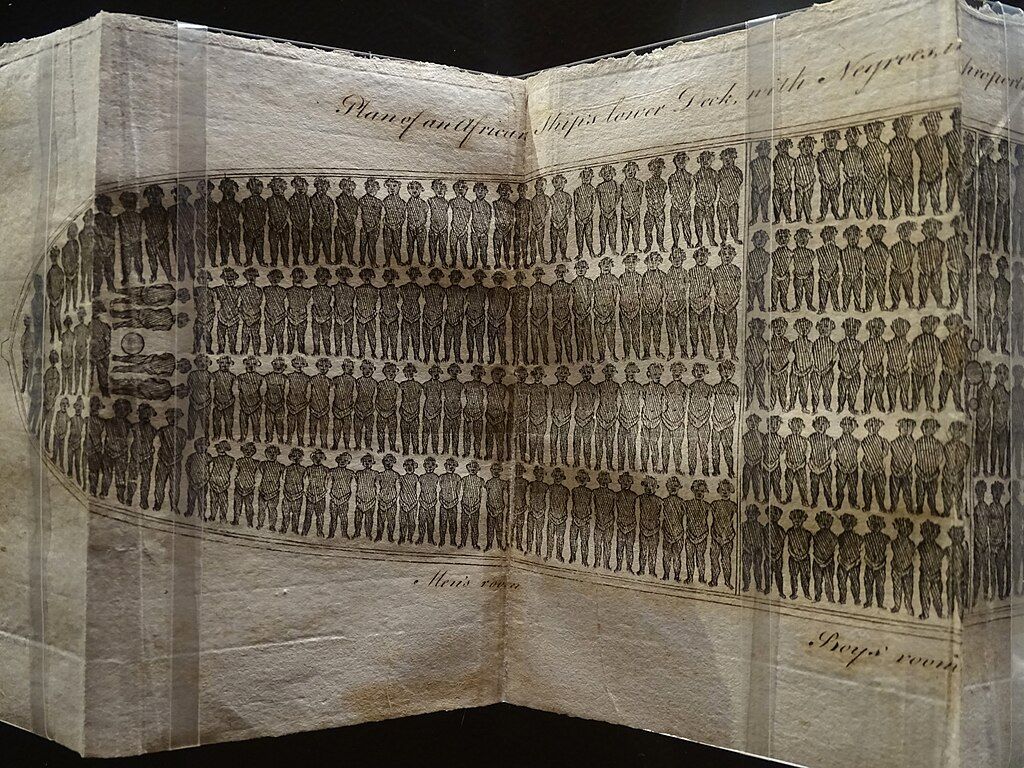

The Middle Passage was a harrowing journey that brought millions of Africans across the Atlantic Ocean to the Americas. This forced voyage, central to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, exposed captives to cramped spaces, rampant disease, and unimaginable suffering. However, resistance remained a powerful theme throughout these voyages. African captives, determined to assert their humanity, found ways to challenge brutal conditions on slave ships, a reality depicted in the slave ship diagram.

Understanding these acts of defiance is essential for appreciating the roots of the antislavery movement. Indeed, African resistance inspired abolitionists—both Black and white—to advocate for justice and equality. Therefore, examining the Middle Passage, the methods of resistance, and the influence of slave ship imagery helps illuminate how enslaved Africans refused to be stripped of their identities. The following sections explore the Middle Passage in detail, highlight the many forms of resistance, and connect these actions to the broader efforts that shaped the antislavery cause.

Understanding the Middle Passage

Definition and Historical Context

The term Middle Passage refers to the forced transatlantic voyage that brought millions of Africans to the Americas. These journeys began after individuals were captured—often through raids or warfare—and sold to European traders at coastal forts and ports. The voyage across the Atlantic could last several weeks or months, during which captives endured overcrowded, unsanitary, and violent conditions aboard slave ships.

For centuries, European and American traders treated African men, women, and children as property to be bought and sold. This system uprooted entire communities, tore families apart, and exposed people to unimaginable suffering—many did not survive the journey. Yet despite these horrors, many Africans resisted dehumanization by preserving their languages, spiritual practices, and cultural traditions. This cultural persistence laid the groundwork for forms of resistance and identity formation described in Learning Objective 2.4.A of AP® African American Studies.

Life Aboard Slave Ships

Slaves on slave ships endured horrific conditions. Stifling heat and cramped quarters were common, with rows of captives forced into spaces barely large enough to move. Disease spread quickly due to poor hygiene, and food shortages often led to malnutrition. Furthermore, traders employed iron restraints or shackles to control movement.

Images of a slave ship from that era, such as the “Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes, Early Nineteenth Century,” provide a visual representation of how enslavers attempted to conserve space—and thereby maximize profit. Although the slave ship diagram claims to show how captives were arranged, real conditions were frequently worse, contributing to despair and fueling the desire for freedom. This was the environment in which countless individuals discovered both quiet and overt ways to resist enslavement.

Methods of Resistance by Africans on Slave Ships

Individual Forms of Resistance

Despite oppressive conditions, Africans on board slave ships remained determined not to be reduced to mere cargo. The most direct expressions of defiance included hunger strikes and attempts to jump overboard. According to EK 2.4.A.1, some captives chose to starve themselves, believing that resisting sustenance was better than enduring a life of enslavement. Others risked everything by leaping into the ocean. These actions sent a clear message: living in bondage was not acceptable.

Individual resilience also surfaced in smaller, everyday ways. Some faked illness or maintained covert communication to ensure that knowledge of their language and culture survived. Even small acts of solidarity—such as sharing secrets or comforting those in despair—kept the flame of hope alive for many who faced an uncertain future.

Collective Resistance

Language barriers posed a serious obstacle on slave ships, especially since captives came from different regions and spoke many dialects. However, mutual oppression brought them together, and they devised ways to overcome linguistic differences (EK 2.4.A.1). Secret planning sometimes involved hand signals or whispered conversations.

In certain cases, the result was open revolt. One of the most iconic examples was the Amistad ship uprising. Collective revolts, though dangerous, were a potent reminder that African captives were not passive victims. Their willingness to fight back, even in the face of dire consequences, challenged the entire idea of enslaving human beings.

Example: Revolt on the Amistad

- The Schooner La Amistad was transporting a group of enslaved Africans in 1839, decades after the official abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Despite laws against such trafficking, these captives found themselves sailing under brutal conditions.

- Sengbe Pieh (also known as Joseph Cinqué) led a revolt that took the ship’s crew by surprise. Overcoming language barriers, the captives coordinated an attack and managed to seize control.

- The aftermath was significant. The trial that followed lasted two years, leading to a Supreme Court decision that granted the Mende captives their freedom. According to EK 2.4.A.3, this high-profile case generated widespread sympathy for abolition, influencing public opinion in the United States and beyond.

Impact of Resistance on the Slave Trade and Slave Ship Design

Economic Consequences

Resistance had tangible effects on the slave trade. Revolts, hunger strikes, and attempts to jump overboard increased financial risks for slave traders. This danger forced them to spend more on security measures, adding to the cost of doing business. Therefore, the profitability of the slave trade slowly declined as rebellions grew more frequent.

Whenever a successful uprising unfolded, enslavers lost both cargo and operational expenses. These factors made some traders question whether the risk was worth the return. This evolution reflected how African defiance, as outlined in EK 2.4.A.2, gradually chipped away at one of history’s most brutal enterprises.

Changes in Ship Design

Shipowners responded to mounting resistance by modifying the architecture of their vessels. Barricades in heavy wooden enclosures were installed to separate enslaved people from each other. Nets stretched around the edges of the ship prevented captives from jumping overboard. Crews often carried more weapons, such as guns, to deter any form of revolt.

These adjustments illustrate how enslavement depended on constant efforts to control human beings who refused to resign themselves to captivity. Despite these measures, Africans continued to challenge their conditions throughout the Middle Passage. The transformation of vessel plans and on-board practices thus became part of a larger, ongoing battle between enslaver and enslaved.

Slave Ship Diagrams: A Window into the Horrors of the Past

Description of the Slave Ship Diagram

Slave ship diagrams were detailed, schematic drawings that provided an outline of how enslavers packed captives below decks. These diagrams were first used to display the inhumane treatment on board but later circulated by abolitionists to illustrate the cruelty of the system. In many of these illustrations, such as those derived from the Brookes slave ship plan, neat rows of figures appear lying shoulder-to-shoulder.

Although a slave ship diagram often depicted hundreds of individuals, it did not fully capture reality. According to EK 2.4.B.1, the drawings usually showed about half the number of people who were actually on board. Moreover, the cramped conditions and overwhelming stench made survival challenging. As a result, many individuals died from disease, malnutrition, or heartbreak before ever reaching the Americas.

The Reality Behind the Diagrams

Slave ship diagrams rarely included certain features designed to prevent captives from revolting. Items like chains, guns, and feeding instruments were often omitted, downplaying how harsh onboard controls could be. In truth, life below deck was suffocating, and compliance was typically enforced through brute force.

A powerful piece connecting past and present is the painting by JMW Turner, known as “The Slave Ship.” This work, though from a slightly later period, underscores the horrifying reality of captives thrown overboard to maximize an insurance claim. Such visual accounts highlight how enslavers viewed their cargo in purely economic terms, underscoring the system’s ruthlessness.

Example: Analysis of a Specific Slave Ship Diagram

- Consider the diagram “Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes, Early Nineteenth Century” linked below. It portrays rows of men, women, and children lying parallel in neat formations.

- The layout reveals an intent to pack in as many captives as possible while still showing a theoretical arrangement that looks systematic.

- Real-life conditions were even more confined, with some ships holding up to double the illustrated number. Guns, barricades, and nets—cited in EK 2.4.B.3—show the lengths to which captains would go to maintain order, revealing the constant battle against determined resistance.

The Legacy of Resistance in the Antislavery Movement

Inspiration for Abolitionists

Acts of defiance on slave ships fueled the antislavery movement by revealing the humanity of captives in the face of brutal oppression. African uprisings on vessels such as the Amistad ship demonstrated the moral and ethical contradictions of slavery. Consequently, Black and white activists realized that slaves were not powerless. Many began to promote these stories to sway public opinion against the slave trade.

Furthermore, diagrams of slave ships—often circulated as proof of abuse—became crucial tools for abolitionists. As noted in EK 2.4.C.1, the images sparked empathy and outrage, prompting calls for change. Public awareness of the cruelty inflicted on enslaved Africans only grew, laying important groundwork for antislavery legislation.

Role of Visual and Performance Arts

Visual symbols have played a vital part in documenting the horrors of the Middle Passage. Artists used paintings, sketches, and performances to highlight the trauma faced by captives and to commemorate acts of courage. Some, like British artist JMW Turner, painted scenes of monstrous cruelty, capturing both the violence and the moral indictment of this system.

Additionally, Black artists have reimagined these visual symbols to honor ancestral suffering and resistance. For instance, Willie Cole’s “Stowage, 1997” uses everyday objects to evoke the cramped spaces of slave ships, each reminiscent of a person once forced into the hull. Such art commemorates the more than 12.5 million Africans taken onto tens of thousands of voyages over several centuries (EK 2.4.C.2). By reworking historical images, contemporary creators ensure these tragic stories remain part of collective memory.

Required Sources and Their Relevance

- Stowage of the British Slave Ship Brookes, Early Nineteenth Century

- This iconic slave ship diagram shows how enslavers tightly packed Africans aboard ships. It demonstrates the commodification of human beings and provides evidence of inhuman conditions, supporting the antislavery movement’s claims about cruelty and profit-seeking motives.

- Plea to the Jurisdiction of Cinque and Others, 1839

- This legal document defends Sengbe Pieh (Cinqué) and his companions in the aftermath of the Amistad revolt. It highlights the moral and legal complexities of enslavement, ultimately leading to a Supreme Court ruling affirming their right to freedom.

- Sketches of the Captive Survivors from the Amistad Trial, 1839

- These drawings humanized the African captives by showing them as individuals with unique identities. This vivid depiction fueled widespread sympathy, advanced abolitionist arguments, and illustrated that those onboard slave ships were far from the faceless property enslavers claimed them to be.

- Stowage, by Willie Cole, 1997

- Cole’s artistic piece reclaims the painful imagery of the slave ship for modern viewers. It offers a contemporary reflection on how historical trauma persists, reinforcing the notion that the memory of the Middle Passage shapes ongoing conversations about justice and equality.

Conclusion

The bravery shown by Africans throughout the Middle Passage is a compelling reminder that, even under the worst circumstances, people will strive for autonomy. Resistance took many forms—individual defiance, collective rebellion, and cultural endurance. Because of these efforts, the Transatlantic Slave Trade faced rising challenges, ship designs changed, and public sentiment shifted toward abolition.

Slave ship diagrams, such as the Brookes plan or JMW Turner’s paintings, remain essential historical records and fire the imagination of artists today. Both then and now, such representations honor the resilience of the captives and shine a light on the moral questions slavery posed. Acts of resistance on slave ships continue to inspire conversations about justice, helping modern audiences reflect on a history that shaped the course of entire nations.

Quick Reference Chart

| Term/Concept | Definition/Key Features |

| Middle Passage | The forced transatlantic voyage of Africans to the Americas that lasted several weeks or months, marked by brutal conditions. |

| Commodification | Treating African captives as goods to be bought and sold, ignoring their humanity and individuality. |

| Amistad Ship | A Spanish schooner seized in a revolt led by Sengbe Pieh in 1839; key legal case eventually granted freedom to the Mende captives. |

| Slave Ship Diagrams | Schematics showing how Africans were arranged on ships (e.g., the Brookes plan), often used by abolitionists to expose cruelty. |

| Individual Resistance | Personal acts of defiance, including hunger strikes and jumping overboard, to reject enslavement. |

| Collective Resistance | Group efforts by captives, sometimes overcoming language barriers to organize revolts, as seen in the Amistad uprising. |

| JMW Turner Slave Ship (“The Slave Ship”) | A painting by Joseph Mallord William Turner depicting enslaved Africans thrown overboard, underscoring the brutality of the trade. |

| Willie Cole’s “Stowage, 1997” | A contemporary artwork that reimagines slave ship imagery to honor ancestral trauma and challenge viewers to reflect on this history. |

| Barricades and Nets | Modifications to slave ships introduced to prevent revolt and stop captives from jumping overboard. |

| Abolition Movement | A campaign to end slavery, bolstered by the stories and images of resistance on slave ships. |

Understanding African resistance on slave ships and its profound influence on the antislavery movement offers a crucial lens through which to explore the broader history of enslavement. These stories demonstrate the enduring strength of the human spirit, challenging each new generation to advocate for justice and preserve the memory of those who fought in the ships’ dark holds.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® African American Studies

Are you preparing for the AP® African American Studies test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® African American Studies problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® African American Studies exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® African American Studies practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.