What We Review

Introduction

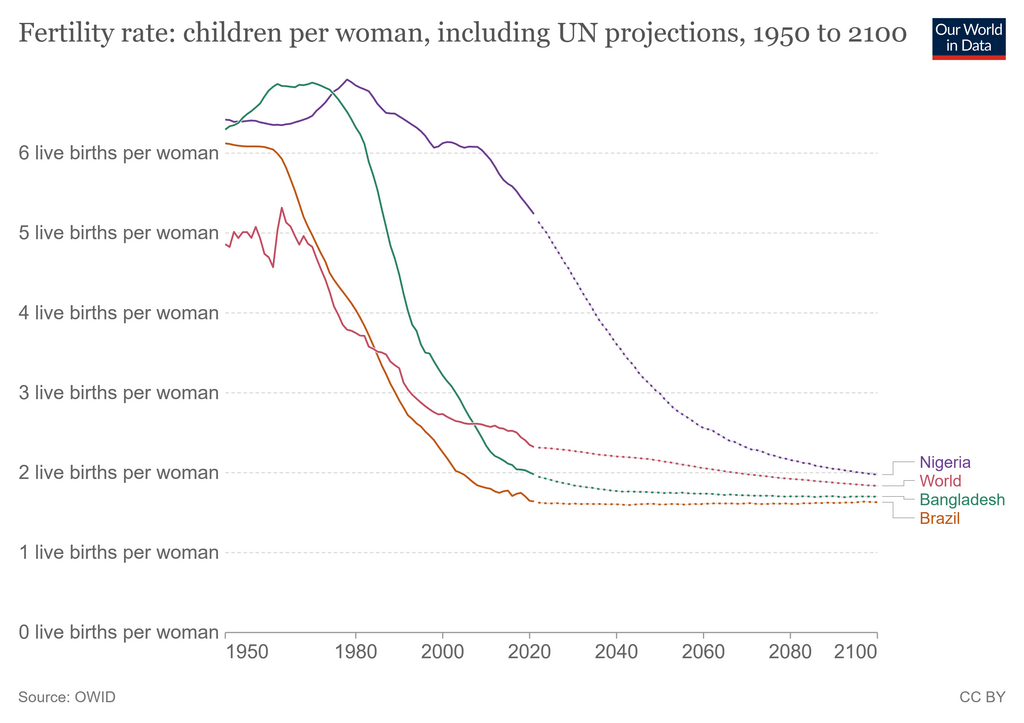

Total fertility rate (TFR) is a crucial concept in AP® Environmental Science because it directly influences human population dynamics. The total fertility rate definition refers to the average number of children a woman is expected to have during her lifetime. This measure indicates how quickly a population might grow or shrink, and it connects to broader environmental issues. Therefore, studying TFR provides a deeper understanding of how societies manage resources, respond to demographic shifts, and shape environmental policies.

Total Fertility Rate Definition

TFR represents the average number of children a woman is expected to have over her reproductive lifetime, assuming current age-specific fertility rates remain unchanged. In mathematical terms, TFR is often summed across various age intervals for a specific population:

\text{TFR} = \sum (\text{age-specific fertility rates} \times \text{length of age interval})However, it is useful to view TFR simply as an estimate of how many children per woman a region’s population is producing on average. In demographic research, TFR is fundamental because it helps explain whether a population is likely to expand, contract, or remain stable.

Another key idea is replacement level fertility. This describes the TFR at which a population exactly replaces itself across generations. In many countries, this “replacement” number hovers around 2.1 children per woman. Values higher than 2.1 usually indicate that a population will grow, while lower values suggest it will eventually shrink.

Factors Affecting Total Fertility Rate

Numerous factors can influence a society’s TFR. Studying these can reveal why different regions exhibit varying population growth rates. The following subsections outline four major contributors: age at first birth, educational opportunities for females, access to family planning, and government policies.

Age at First Birth

The age at which females have their first child can significantly affect TFR. When the average age of first-time mothers is relatively low, women tend to have more children overall because their childbearing years span a longer period. Conversely, when the age at first birth is higher, there is less opportunity to have multiple births.

- Example: In some developing nations, many women start families in their late teens. As a result, the overall TFR tends to be higher. By contrast, in certain European countries where the age of first motherhood frequently exceeds 30, the TFR is often below replacement levels.

Educational Opportunities for Females

Educational achievement among females plays one of the strongest roles in determining TFR. Women with more years of schooling generally delay marriage and childbearing, which often reduces the total number of children they have. Moreover, increased education empowers women to make informed reproductive decisions.

- Example: In nations such as South Korea, where women are highly educated, TFR levels have fallen well below replacement. This shift not only stems from personal choices but also from the economic implications of child-rearing in modern societies. Consequently, the country must adjust its policies to address declining birth rates over time.

Access to Family Planning

Access to family planning services, including contraception and reproductive health resources, can help individuals and couples control the number and spacing of their children. As a result, communities with robust family planning programs often have lower TFR values. Better access also tends to improve maternal and infant health, since planned pregnancies reduce medical complications.

- Example: Suppose a local clinic introduces a comprehensive family planning program in a semi-rural area. Over the next several years, this community’s TFR could drop noticeably due to the availability of different contraceptive methods. As families gain more autonomy over childbearing, they might choose smaller family sizes.

Government Policies and Acts

Certain government regulations or incentives may nudge TFR up or down. Policies range from providing financial benefits for multiple children to limiting the number of children per family. Governments may also invest in healthcare and social support that indirectly affects birth rates.

- Example: China’s One-Child Policy, introduced in 1979, dramatically reduced the nation’s TFR. Designed to curb rapid population growth, the policy restricted many families to only one child. Although the policy was later relaxed, its impact continued to shape China’s demographic structure for decades afterward.

The Relationship Between TFR and Infant Mortality Rate

TFR often links to the infant mortality rate, defined as the number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births in a given year. When infant mortality is high, parents may have more children to offset the likelihood of losing one or more to preventable diseases. Therefore, society’s healthcare systems and nutritional resources become critical factors: where mothers and infants receive adequate medical care, TFR may trend lower because the survival rate of children improves.

- Example: Consider two countries with distinct infant mortality rates. Country A has excellent prenatal care, advanced neonatal facilities, and a low infant mortality rate of about 3 deaths per 1,000 live births. Its TFR, in turn, sits close to replacement level or below. In contrast, Country B faces poor healthcare infrastructure and an infant mortality rate exceeding 50 deaths per 1,000. Parents in Country B might plan for larger families, leading to a higher TFR. Over time, improvements in healthcare access could gradually lower both infant mortality and TFR.

Stability of Human Populations

When TFR stays at replacement levels (about 2.1 children per woman in many industrialized nations), a population is considered relatively stable. Such stability suggests that each generation is large enough to replace the previous one, but not large enough to spark rapid growth. However, if TFR dips significantly below replacement, an aging population and workforce shortages may emerge. On the other hand, if TFR rises too high, a society might face increased demand for jobs, schooling, housing, and natural resources.

- Example: Historical data on TFR in the United States shows that after peaks in the mid-20th century (the “Baby Boom”), the rate eventually settled closer to replacement levels. This change influenced the structure of society, housing development, and resource consumption patterns. Many nations have seen similar shifts, moving from high TFR to near or below replacement once economic conditions and social structures evolve.

Implications of Changing TFR

Shifts in TFR generate repercussions for sociocultural structures, economies, and the environment. Many AP® Environmental Science topics, including resource availability and planning for sustainable development, connect directly to population dynamics.

Sociocultural Effects

Cultural norms shape family size expectations, and these norms can evolve due to changing TFR. A lower TFR might lead to smaller average household size, affecting future education needs, housing design, and community support systems for older adults. Conversely, a higher TFR might preserve traditional beliefs around large families, yet can strain local educational and healthcare infrastructures.

Economic Impacts

In many nations, economic growth depends on maintaining a balanced workforce. When TFR sinks below replacement, the labor force can begin to shrink, making it difficult to sustain programs such as pensions and healthcare for retirees. Yet rapid population growth from a high TFR can also challenge economies, since more schools, jobs, and infrastructure become necessary to accommodate a younger, rapidly expanding population.

Effects on the Workforce:

- Labor shortages or surpluses

- Shifts in demand for education and job training

- Pressure on social security systems in aging societies

Environmental Considerations

Environmental sustainability depends on balancing resource use with population size. Faster-growing populations may put pressure on land, water, and energy resources. This can accelerate deforestation, pollution, and climate change contributions unless policies and practices are well-managed. Meanwhile, nations with growing populations must also consider renewable energy implementation, sustainable farming methods, and waste management strategies.

It is crucial to remember, however, that population change is not the only factor affecting the environment. Technology, resource consumption patterns, and governmental regulations also shape environmental outcomes. Nevertheless, TFR remains a key demographic indicator that often predicts long-term environmental impacts.

Conclusion

Total fertility rate (TFR) serves as a cornerstone of understanding human population dynamics in AP® Environmental Science. By examining factors such as the age at first birth, educational opportunities for females, access to family planning, and government policies, it becomes clear how TFR influences both current and future societal development. Furthermore, the link between TFR and infant mortality rates highlights the importance of healthcare access for mothers and children, reinforcing that population statistics correlate deeply with public health outcomes.

Ultimately, when TFR aligns with replacement-level fertility, populations may stabilize. However, variations above or below that threshold can signal significant demographic shifts that affect social, economic, and environmental systems. Awareness of these factors allows future policymakers, environmental scientists, and communities to plan for sustainable growth that addresses resource limitations, promotes equity, and safeguards ecosystems.

Key Vocabulary

- Total Fertility Rate (TFR): The average number of children a woman is expected to have during her lifetime based on current age-specific fertility rates.

- Replacement Level Fertility: The level of fertility at which a population exactly replaces itself from one generation to the next, often around 2.1 children per woman.

- Infant Mortality Rate: The number of infant deaths per 1,000 live births in a given year, serving as an indicator of healthcare quality and nutrition.

- Family Planning: The practice of controlling the number and spacing of children through methods like contraception, counseling, and health services.

- Age at First Birth: The average age at which females in a population have their first child, influencing the overall total fertility rate.

- Government Acts and Policies: Rules or guidelines imposed by governments that can either encourage or limit the number of children families choose to have.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Environmental Science

Are you preparing for the AP® Environmental Science test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Environmental Science problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- AP® Environmental Science: 3.3 Review

- AP® Environmental Science: 3.4 Review

- AP® Environmental Science: 3.5 Review

- AP® Environmental Science: 3.6 Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Environmental Science exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Environmental Science practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.