What We Review

Introduction

The tragedy of the commons is a central concept in AP® Environmental Science that addresses how shared resources may be overused when everyone acts in self-interest. This idea reminds students that individuals often exploit common property rather than protect it for the collective good. Understanding this concept is crucial because environmental challenges, such as overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction, often stem from competing individual priorities. Moreover, learning practical solutions and reviewing tragedy of the commons examples provides insight into balancing personal gains with responsible stewardship of communal resources.

The following sections break down the tragedy of the commons, examine real-world scenarios, and highlight strategies to curb these resource misuse patterns. Each example is explained step by step to clarify why these challenges occur and how communities, governments, and innovators can intervene.

Definition of the Tragedy of the Commons

The tragedy of the commons describes situations in which individuals, pursuing their own goals, deplete shared resources to the detriment of everyone. Historically, the term “commons” refers to land shared by villagers for grazing livestock or gathering resources. Nineteenth-century economist William Forster Lloyd discussed this issue early on, but it was ecologist Garrett Hardin’s 1968 essay that popularized the phrase.

Hardin argued that when a resource is open-access—where no one person owns it—there is little financial or social incentive to protect it. Consequently, individuals may withdraw or exploit more than their fair share, hoping to benefit before others do the same. However, this leads to a vicious cycle, causing resources to become degraded or vanish entirely.

How It Works

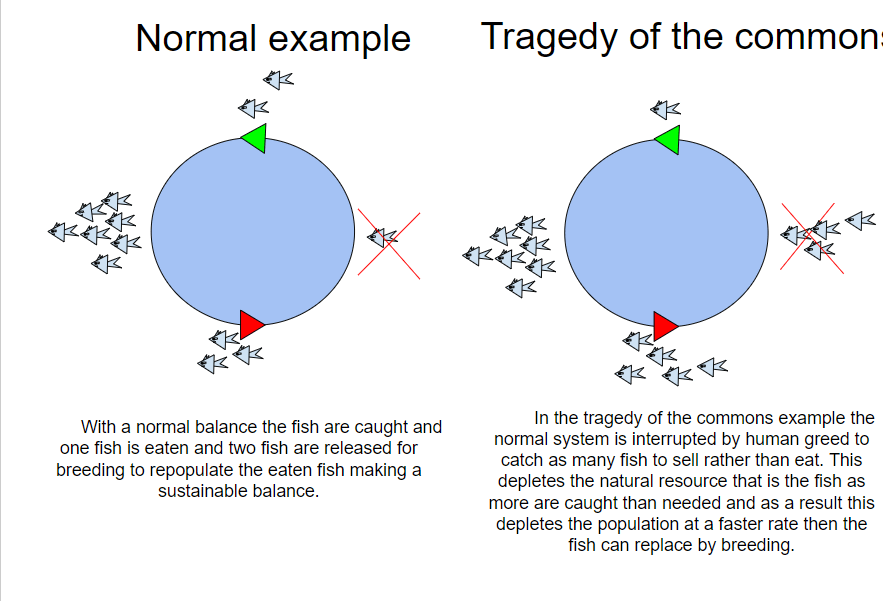

At its core, the tragedy of the commons reveals a mismatch between short-term individual incentives and long-term collective interests. Each person tends to act in a manner that seems logical in the moment. However, when many individuals behave this way, the negative impacts quickly accumulate. As the resource diminishes, everyone suffers setbacks.

Step-by-Step Example: Overfishing

- Fisher A notices a healthy population of fish in a public lake.

- Fisher A increases fishing efforts, taking more fish than the sustainable limit, hoping to maximize personal profit.

- Fisher B observes advertisements or local rumors about abundant catches, then also decides to catch more.

- Soon, multiple fishers compete by using advanced nets, larger boats, or more fishing gear.

- Because everyone is focusing on immediate gain, no one invests in long-term resource stewardship.

- Eventually, the fish population drops below the level required to replenish itself naturally.

- The entire community suffers from reduced catches, higher prices, or even a total collapse of the fishery.

This sequence often appears in environmental scenarios involving shared resources, and it highlights the universal risks of unregulated access. Therefore, management strategies that encourage individuals to account for collective well-being are fundamental in preventing such outcomes.

Real-World Examples

Real-world applications of the tragedy of the commons can be seen in many spheres, ranging from agriculture to urban development. The following examples illustrate important resource dilemmas.

Example 1: Overgrazing

Overgrazing occurs when too much livestock feed on the same piece of land without sufficient recovery time for vegetation. Historically, village commons provided pasture space to multiple herders, each free to graze their animals. However, if all herders try to maximize their livestock numbers, vegetation does not regenerate, and land productivity declines.

- A shared grazing field is used by several herders.

- Each herder adds a few more animals, expecting to earn more income from meat or wool.

- Despite signs of stress on the grass, herders hesitate to reduce their livestock, fearing others might continue grazing at high levels.

- As animal numbers grow, plants struggle to regrow quickly, eventually leading to soil degradation.

- Once the soil erodes and grass becomes scarce, everyone experiences feeding shortages for their herds.

- Consequently, local economies suffer, and the land may require years or expensive remediation efforts to recover.

This chain of events shows why everyone’s actions matter. Furthermore, it underlines the necessity for defined limits, rotational grazing schedules, or other conservation measures to safeguard rangeland health.

Example 2: Pollution

Pollution also fits the tragedy of the commons framework, especially when individuals pollute shared resources such as the air or water supply. The resulting harm extends beyond any single polluter to affect entire communities.

Air Pollution

Industrial facilities, cars, and power plants emit pollutants into the atmosphere, potentially degrading air quality for entire regions. If each source of emissions follows only self-interest and tries to reduce costs by avoiding more expensive, cleaner technology, particulate matter and gases accumulate, threatening public health and ecosystems.

Step-by-Step: A Polluted River

- Factories along a river dispose of waste by releasing it into the water.

- Downstream, towns notice reduced water quality and the disappearance of fish that once sustained local economies.

- Each polluter, acting individually, believes that one plant’s waste is minimal compared to other factors.

- Because each source assumes others are doing the same, little incentive exists to invest in cleaner methods.

- Contamination rises until the river becomes unsafe for drinking, agriculture, or recreation.

- Heavy cleanup efforts, new laws, or even lawsuits may become necessary to restore safe conditions.

Over time, communities in such situations typically move toward local regulations or cooperative agreements. Otherwise, the resource’s final depletion can lead to lasting economic and social difficulties.

Solutions to the Tragedy of the Commons

Multiple strategies exist to mitigate the tragedy of the commons. These solutions revolve around shaping individual actions to align with the shared vision of sustainable resource use. Moreover, they often combine regulatory measures, community-driven rules, and technological tools.

- Government Regulations

- Governments play a central role by setting catch limits, creating protected areas, or restricting harmful activities. For instance, a fishery may assign quotas that limit how many fish each boat can harvest. This approach promotes equitable distribution and encourages fishers to sustain stocks rather than race against one another.

- Community Management

- Local communities often use agreements or cooperatives to regulate member behavior. Enforcement might include rotating grazing zones, assigning specific fishing times, or setting strict waste disposal guidelines. This approach works well when social norms and peer pressure reinforce compliance.

- Technological Innovations

- Improved technology can make certain extraction methods more sustainable. For example, advanced water filtration systems can clean industrial discharge to protect rivers. Renewable energy sources reduce the need for fossil fuels, thereby lessening air pollution. Additionally, digital tracking of resource usage can inform harvest quotas or ensure that each user remains within a fair share.

Successful Implementations

- In certain fishing regions, community-based fishery management programs employ real-time catch data. This feedback loop helps enforce daily or seasonal limits.

- Many ranchers now adopt rotational grazing practices that sequentially move livestock among designated paddocks. This method allows grasslands to regenerate, maintaining soil stability and carbon cycle balance.

- Some factories invest in cleaner technologies or adopt zero-liquid-discharge systems, meaning water is reused within the facility. These measures lessen ecological harm and reduce resource depletion in rivers.

All these solutions emphasize that cooperation and accountability prevent shared resources from collapsing. In addition, they encourage a mindset that considers the future value of natural resources, not just immediate gain.

Conclusion

The tragedy of the commons demonstrates how simply pursuing personal benefits can create severe negative outcomes for entire communities. While it may feel logical in the short term to use as many resources as possible before others do, the end result frequently causes significant harm for everyone. Whenever common goods—such as pastures, fisheries, or water sources—are open-access, unregulated use risks depleting them entirely.

Therefore, collective responsibility becomes essential. Cooperative arrangements, thoughtful regulation, and innovative technology encourage more balanced resource consumption. Whether in a local neighborhood managing shared recreational spaces or in global efforts to protect ocean fisheries, strategies must align individual interests with the greater good. This approach helps preserve resources for current and future generations, reinforcing the fundamental principles explored in AP® Environmental Science.

Key Vocabulary

- Tragedy of the Commons: The phenomenon in which individuals overuse a shared resource, leading to depletion or degradation of that resource over time.

- Open-Access Resource: A natural resource that has no specific ownership, making it prone to overuse when many users share it.

- Overgrazing: The depletion of vegetation due to excessive feeding by livestock on the same land area without adequate recovery periods.

- Pollution: The introduction of harmful substances into air, water, or land, which damages ecosystems and human health.

- Rotational Grazing: A method of moving livestock periodically from one pasture to another, allowing vegetation to rest and regenerate.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Environmental Science

Are you preparing for the AP® Environmental Science test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Environmental Science problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- AP® Environmental Science: 4.7 Review

- AP® Environmental Science: 4.8 Review

- AP® Environmental Science: 4.9 Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Environmental Science exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Environmental Science practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.