What We Review

The Social Construction of Race and the Reproduction of Status

Understanding race as a social construct is essential for grasping how certain laws, beliefs, and customs shaped the lives of African Americans. Concepts such as partus sequitur ventrem, phenotype, the one-drop rule, and various racial taxonomies all played a major role in defining who was considered enslaved or free. Recognizing how these ideas developed helps explain why racial identity became so vital in American history.

Below is a clear look at how each concept influenced African American communities, both in the past and today.

What Is Race?

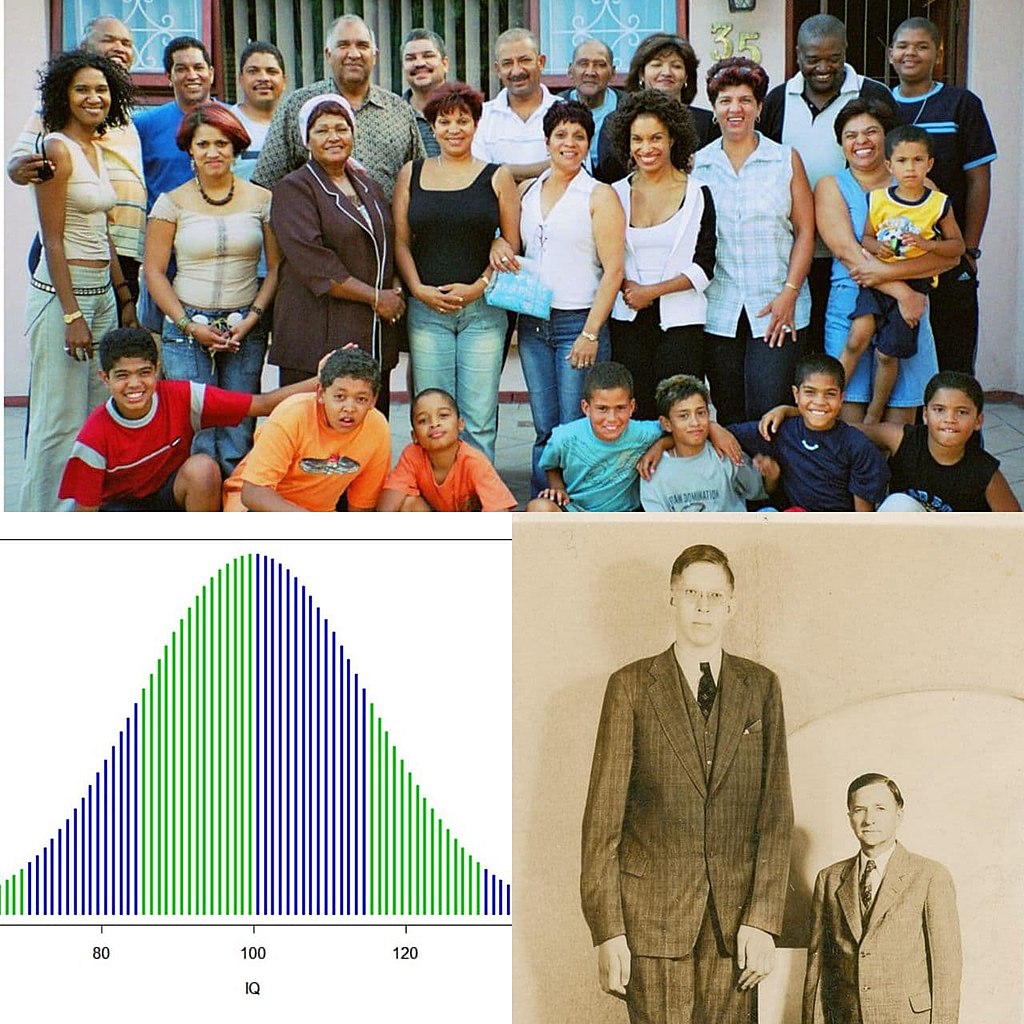

Race can be understood as a way society groups people based on certain physical appearances, such as skin color or hair texture. Many believe that race is only about biology, but scholars in African American Studies and other fields view “race and social construction” as closely tied. In other words, people create ideas about race rather than simply discover them in nature.

Social vs. Biological:

- Biological definitions suggest that race is rooted in genetics. However, there is often more genetic variation within one so-called race than between people of different races.

- Social definitions argue that each community decides how individuals are classified, granting or denying privileges based on these categories.

For example, in one society, a person with mixed ancestry might be seen as one race, while in another society, that same person might be seen as a separate race. These shifting perceptions influence identity, opportunities, and how others treat an individual.

The Concept of Partus Sequitur Ventrem

Partus sequitur ventrem (meaning ‘that which is born follows the womb’ in Latin) is a seventeenth-century law that declared a child’s legal status based on the status of the mother. This law first appeared in the colony of Virginia. According to this rule, if the mother was enslaved, so was the child. This policy had far-reaching consequences:

- It ensured that slavery could continue across generations.

- It invalidated the rights of African American mothers to claim their children’s freedom.

- It gave male enslavers the power to avoid responsibility for children fathered through assault or exploitation.

A Historical Example

Imagine an enslaved woman named Sarah living on a Virginia plantation in the late 1600s. If Sarah had a daughter, that daughter would automatically be enslaved, regardless of the father’s status. Consequently, every child born to Sarah and her daughters would inherit slavery. This cycle continued through multiple generations, linking Black identity to permanent enslavement and reinforcing a caste-like system.

Racial Taxonomies and Their Evolution

Racial taxonomies are systems for classifying people by race. During the era of enslavement, these categories evolved to support economic and political structures tied to slavery. The laws and customs defining who was “Black” or “White” were not consistent across all regions, producing confusion and injustice.

1. Different States, Different Definitions

- Before the Civil War, states varied in their rules. Some used specific fractions of African ancestry to determine race (for instance, one-quarter or one-eighth).

- Consequently, two individuals with similar family backgrounds, living in different states, might be classified differently.

2. Connection to Slavery

- Racial classifications often linked directly to whether a person was enslaved or free.

- Authorities used these definitions to maintain control over economic systems that relied on enslaved labor.

A Contrast of Two Individuals

Consider two men, James and Henry, living during the early 1800s:

- Both have ancestors of European and African descent.

- In one state, James would be legally labeled as “Black” because he has an African American grandparent.

- Henry, living in another state, might be recognized as “White” if the state used a stricter fraction for determining Black identity.

These inconsistencies reveal how flexible and imperfect racial categories were. Rather than reflecting true biology, legal systems made the rules.

Phenotype and Its Role in Race

Phenotype refers to visible traits, such as skin color, hair texture, and facial features. During slavery, lawmakers and communities often used these traits to place individuals into racial categories. However, phenotype alone was not always the deciding factor. Legal definitions—like partus sequitur ventrem—could overpower physical appearance when determining a person’s status.

Comparing Two Individuals

Imagine two relatives, Marcus and Clara, who share many physical traits. Both have medium-brown skin tones and curly hair. In certain situations, Marcus might have been considered free, perhaps due to legal documents confirming his mother’s free status. Clara, lacking the same proof, might have remained enslaved, despite their similar appearance. Phenotype alone did not guarantee freedom or equality.

The One-Drop Rule and Racial Classification

The one-drop rule was a practice in the United States, especially after the Civil War, stating that a person with any African ancestry was considered Black. This rule is a form of hypodescent, where mixed-race individuals inherit the status of the lower-ranking group in society.

- If a person had a Black grandparent, they were often classified as Black, no matter how European their other relatives were or how they looked physically.

- This classification maintained a system that prevented many individuals from fully claiming a multiracial or multiethnic heritage.

A Realistic Scenario

Suppose an individual named Abigail had three White grandparents and one African American grandparent. The one-drop rule would categorize Abigail as Black. With that label, she would likely face the same discriminatory practices affecting the Black community. In contrast, if she had lived in certain other countries, she might be categorized differently.

The Impact of Racial Constructs on Society

These constructs—partus sequitur ventrem, racial taxonomies, phenotype race classifications, and the one-drop rule—did not exist only on paper. They shaped daily life for African Americans, influencing everything from educational access to job opportunities. Large-scale consequences included:

- Legal Marginalization: Laws often denied land ownership, voting rights, and fair wages to those considered Black.

- Social Barriers: Widespread discrimination in housing, marriage, and public accommodations limited social mobility.

- Economic Inequality: Persistent exploitation and low wages created systemic poverty in many African American communities.

When examining the legacy of these ideas, it becomes clear they left structural inequalities that continue to affect people today. Understanding this history helps explain current disparities in wealth, education, and health care.

Required Sources and Historical Context

“Laws of Virginia, Act XII, General Assembly, 1662”

This historic legislation formalized partus sequitur ventrem in the colony of Virginia. It declared that children “shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.” This law linked Black identity to hereditary slavery, guaranteeing a perpetual labor force.

In the context of this article’s topic, Act XII provides direct evidence of how legal systems codified racial slavery. By defining status through the mother, Virginia’s legislators created an official pathway for slavery to continue indefinitely.

“Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” from The Liberator, 1849

Published in an anti-slavery newspaper, this illustration emphasized the moral and human rights of enslaved women. Although originally a slogan for abolition, the phrase highlights the injustice of denying African American women’s rights to their children. This sentiment directly connects to partus sequitur ventrem, which stripped mothers of any claim to protect their children from enslavement.

Both sources show how race and social construction were intertwined. Laws of Virginia, Act XII, 1662, revealed the state’s power to define a child’s status as enslaved. “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” appealed to public empathy, challenging the very logic behind enslaving mothers and children.

Conclusion

Race has long been shaped by social and legal conventions rather than by biology alone. Partus sequitur ventrem, phenotype-based classifications, racial taxonomies, and the one-drop rule worked together to keep African Americans in a lower social position. By recognizing how laws and customs have defined race, individuals today can see why racial issues persist. This understanding also encourages further study of African American history and the powerful forces that shaped it.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a summary of important terms and concepts:

| Term | Definition |

| Social Construction of Race | The idea that racial categories are created by societies and government policies, rather than by clear-cut biological facts. |

| Partus Sequitur Ventrem | A 17th-century law stating that a child’s legal status follows the mother’s status. If the mother was enslaved, her children were also enslaved. |

| Phenotype | Visible physical traits, such as skin color and hair texture, that influence how a person’s race is often perceived. |

| Racial Taxonomies | Systems used to classify people based on their ancestry or physical appearance, often leading to unequal treatment and enforcement of slavery. |

| Hypodescent | A practice in which a child born of mixed ancestry is automatically assigned the racial status of the lower-status parent group, reinforcing social hierarchies. |

| One-Drop Rule | A classification stating that any person with even “one drop” of African ancestry is considered Black, limiting the acknowledgment of multiracial identities. |

| Laws of Virginia, Act XII | A 1662 Virginia law that established partus sequitur ventrem, effectively tying future generations to slavery if their mothers were enslaved. |

| “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” | A powerful anti-slavery image from 1849 highlighting the moral horrors of slavery, particularly focusing on the experiences of enslaved women. |

These concepts illustrate how race has been molded by law, social customs, and economic motivations. Recognizing their historical context is key to understanding the roots of modern racial identities and inequalities.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® African American Studies

Are you preparing for the AP® African American Studies test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® African American Studies problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

Need help preparing for your AP® African American Studies exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® African American Studies practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.