Classical conditioning is a core concept in psychology that examines how organisms learn to link one stimulus with another. This type of learning can shape behavior and mental processes, giving researchers key insights into why individuals respond in certain ways. Therefore, mastering classical conditioning helps explain real-world behaviors, from simple reflexes to complex emotional reactions. In many cases, it provides a foundation for therapeutic interventions, such as counterconditioning for phobias.

This article will define classical conditioning psychology, explore its main components, and include examples at each step. Readers will also find a helpful reference chart of important vocabulary toward the end. Understanding these details is crucial for any student looking to learn how stimuli and responses connect in the behavioral perspective.

What We Review

Defining Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning occurs when a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a stimulus that naturally produces a response. This neutral stimulus eventually triggers a similar response, now called a conditioned response.

Key components include:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS): A stimulus that elicits a natural, automatic reaction (response) without prior learning.

- Unconditioned Response (UCR): The natural reaction caused by the UCS.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): A previously neutral stimulus that now triggers a response after repeated association with the UCS.

- Conditioned Response (CR): The learned reaction to the CS, which mirrors the UCR but is triggered by the CS alone.

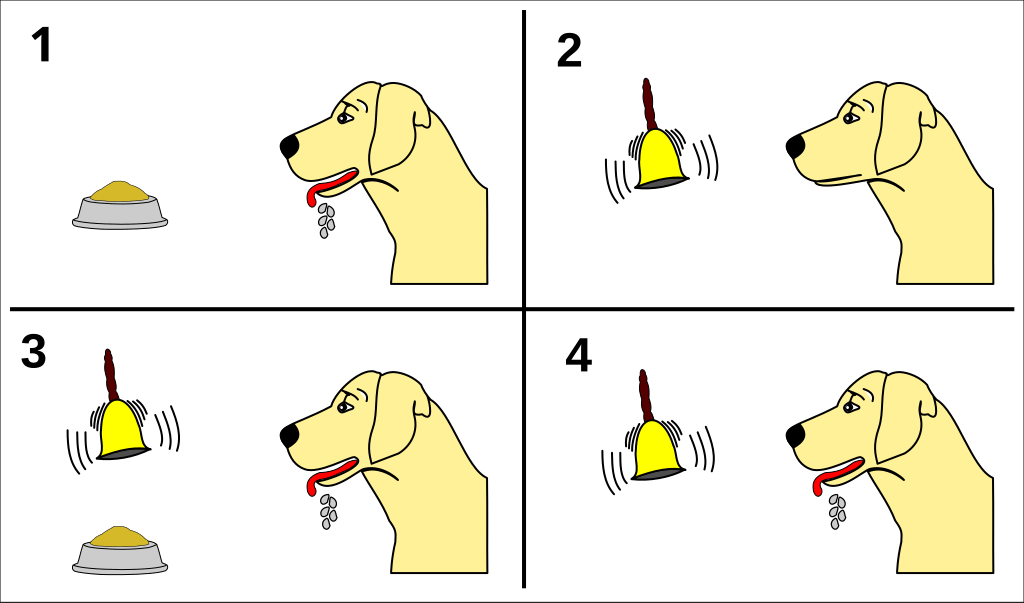

Example: Pavlov’s Dogs

In one of the most famous classical conditioning examples, Ivan Pavlov presented dogs with food and noticed they began to salivate naturally.

Step-by-Step Breakdown

- Before training, the food (UCS) automatically caused salivation (UCR).

- Pavlov rang a bell (initially a neutral stimulus) before presenting the food.

- After several pairings, the bell alone (now CS) made the dogs salivate (CR).

This process shows how a neutral stimulus can gain the power to elicit a response once paired with an unconditioned stimulus.

The Process of Classical Conditioning

The sequence for successful classical conditioning often follows this pattern:

- The CS consistently precedes the UCS.

- Timing between the CS and UCS is crucial.

- The learner acquires the association through repeated trials, known as acquisition.

According to AP® Psychology guidelines (3.7.A.2), the order of CS with the UCS strongly influences whether a conditioned response is learned.

Example: Pairing a Bell with Food

Imagine a scenario where a person rings a small bell right before giving a dog a treat.

Step-by-Step Illustration

- The dog hears the bell (neutral stimulus).

- Immediately afterward, the dog receives the treat (UCS) and begins to salivate (UCR).

- Repeating this process leads the dog to connect the bell’s sound (CS) with receiving food (UCS).

- Eventually, the dog salivates (CR) at the sound of the bell alone.

The critical factor is that the bell sounds right before the treat is given. If the sequence is reversed or poorly timed, the association may not develop.

Extinction in Classical Conditioning

Extinction happens when the conditioned stimulus no longer predicts the unconditioned stimulus. Over time, the conditioned response weakens and might disappear. However, this does not always mean that the learning is permanently erased.

In many cases, spontaneous recovery can occur. This term refers to the reappearance of a weakened conditioned response after the passage of time, even if it seemed to have vanished.

Example: Bell No Longer Predicts Food

Imagine a situation in which the dog hears the bell repeatedly but does not receive any treat.

Step-by-Step Explanation

- The bell (CS) starts to lose its meaning when it is no longer followed by food (UCS).

- With each trial, salivation (CR) decreases.

- After multiple sessions, the dog shows no salivation, indicating extinction.

- Later, the bell may still trigger a slight response if food is again presented shortly after the bell, demonstrating spontaneous recovery.

Extinguishing a response requires withholding the UCS long enough for the learned association to fade.

Generalization and Discrimination

After learning a conditioned response, organisms can generalize similar stimuli or learn to discriminate between them.

- Stimulus Generalization: Responding to stimuli that resemble the original CS.

- Stimulus Discrimination: Learning to distinguish which stimuli will lead to the UCS and which will not.

These aspects are central to understanding how certain fears or preferences can spread to related stimuli or become more narrowly focused.

Example: Fears of Dogs

- Generalization: A child bitten by one dog (CS) may later fear all dogs (similar stimuli).

- Discrimination: The same child may learn to respond with caution only to large dogs while feeling comfortable around smaller breeds.

Step-by-Step Process

- A dog bite (UCS) causes a fear response (UCR).

- A specific dog, such as a large black dog, becomes the CS.

- The fear (CR) might initially extend to all dogs (generalization).

- With time, the child learns discriminative cues, responding only to certain dogs and not others.

This ability to differentiate helps reduce unnecessary fear or anxiety responses.

Higher-Order Conditioning

Classical conditioning can also occur when a conditioned stimulus plays the role of an unconditioned stimulus in a new association. This process is known as higher-order conditioning.

A neutral stimulus, when paired with an existing CS, can become another conditioned stimulus. However, the response typically weakens with each new level of conditioning.

Example: Pairing a Light with a Bell

Suppose a light is introduced along with the bell, which already signals food.

Step-by-Step Illustration

- The bell is established as a CS that prompts salivation (CR).

- A light (a new neutral stimulus) is switched on just moments before the bell is rung.

- After several pairings, the dog salivates when the light alone is turned on because it predicts the bell’s signal for food.

- The light now becomes a secondary CS, although the salivation might be weaker.

This chain-like process highlights how learning can stack in layers, but the conditioned response may diminish in strength.

Emotional Responses and Classical Conditioning

Research (3.7.A.3) indicates that emotional responses can be classically conditioned. This helps us understand how certain feelings become triggered by specific cues. Moreover, therapists use approaches such as counterconditioning to replace negative emotional associations with neutral or positive ones.

Example: Overcoming a Phobia

A child fearful of thunderstorms may be guided through systematic desensitization, where a calming stimulus is paired with gentle thunder sounds.

Step-by-Step Method

- The therapist presents a calming image (CS) alongside a very faint thunder sound (UCS that causes fear).

- Gradually, the thunder sound is increased in volume, always paired with the calming image.

- Over time, the child’s anxiety (CR) lessens due to the new association between calmness and thunder.

- This method progressively reduces the emotional intensity linked to storms.

Such techniques illustrate how classical conditioning shapes emotional behavior and can be harnessed to alleviate anxiety or phobias.

Taste Aversions and One-Trial Learning

Taste aversion occurs when an organism associates a particular flavor with illness or discomfort, often after just one exposure. This rapid learning, known as one-trial learning, exemplifies how biology can prepare organisms to avoid harmful substances.

Example: A Distaste for Seafood

A person who eats shellfish and later becomes sick might find the smell or taste of shellfish nauseating.

Step-by-Step Explanation

- The shellfish meal acts as a UCS, causing sickness (UCR).

- The taste and smell of shellfish become the CS.

- Even after one time, future exposure to shellfish (CS) triggers discomfort (CR).

- This strong aversion persists because the individual’s body treats shellfish as a warning.

Biological preparedness plays a role here, as it supports quick learning for survival-related stimuli.

Habituation vs. Classical Conditioning

Habituation is distinct from classical conditioning. It involves becoming less responsive to a repeated stimulus that does not carry significant consequences. In contrast, classical conditioning depends on forming an association between two events.

Example: Getting Used to a Background Noise

A student who moves to a city apartment may initially feel distracted by traffic, but soon notices it less and less.

Step-by-Step Clarification

- The traffic noise is new and triggers a startled response.

- Over time, if the noise is not threatening, the student’s attention to it fades.

- Conversely, if the noise predicted something significant, classical conditioning could occur.

- In habituation, the response simply weakens due to repetition.

This distinction helps explain why repeated harmless stimuli may become ignored while other stimuli that signal events (like treats or danger) produce a lasting response.

Conclusion

Classical conditioning is a foundational framework in psychology that illustrates how behavior can be molded by forming associations. By understanding concepts such as UCS, UCR, CS, and CR, psychologists can predict and influence responses. Furthermore, phenomena like extinction, spontaneous recovery, stimulus generalization, and higher-order conditioning reveal the complexity underlying learning processes. These principles have practical applications in therapy, emotional responses, taste aversions, and more.

In short, classical conditioning remains a vital tool for explaining how stimuli shape behavior and mental processes. By mastering these principles, one can better appreciate both everyday behaviors and targeted interventions designed to modify problematic responses.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a quick reference chart that summarizes important vocabulary and definitions related to classical conditioning.

| Vocabulary Term | Definition |

| Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS) | A stimulus that naturally triggers a response without any prior learning. |

| Unconditioned Response (UCR) | The natural response that occurs in reaction to the unconditioned stimulus. |

| Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | A previously neutral stimulus that, after becoming associated with the unconditioned stimulus, eventually comes to trigger a conditioned response. |

| Conditioned Response (CR) | The learned response to the previously neutral stimulus that has been paired with the unconditioned stimulus. |

| Acquisition | The process of learning the association between the conditioned stimulus and unconditioned stimulus. |

| Extinction | The gradual weakening and disappearance of a conditioned response when the conditioned stimulus is presented without the unconditioned stimulus. |

| Spontaneous Recovery | The reappearance of a conditioned response after a rest period following extinction. |

| Stimulus Generalization | The tendency to respond to stimuli that are similar to the conditioned stimulus. |

| Stimulus Discrimination | The ability to distinguish between the conditioned stimulus and other stimuli. |

| Higher-Order Conditioning | The process of conditioning a second conditioned stimulus (CS) by pairing it with the first conditioned stimulus (CS). |

| Taste Aversion | A type of classical conditioning where an individual associates a specific food with illness, often achieved after just one pairing (one-trial learning). |

| Habituation | A decrease in response to a repeated stimulus over time, leading to diminished reactions. |

These terms and their explanations provide the building blocks for understanding how classical conditioning and behavior connect. This knowledge is integral to many branches of psychology, including behavior modification, therapy, and research into learning processes.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Psychology

Are you preparing for the AP® Psychology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Psychology problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- Developmental Psychology: AP® Psychology Review

- Physical Development: AP® Psychology Review

- Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity: AP® Psychology Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Psychology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Psychology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.