What We Review

Understanding social-emotional development helps show how social experiences shape behavior and mental processes. This topic explores events from infancy to adulthood, highlighting how relationships and cultural factors affect each stage of life. The sections below explain key theories and concepts step by step, using real-world examples.

Introduction

Social-emotional development refers to how individuals learn to interact with others and manage their feelings throughout their lives. It includes understanding one’s own emotions, forming healthy friendships, and adapting behavior in different environments.

It is important to study social development and mental processes because they influence every aspect of life. For instance, the way a person responds to stress or builds relationships often depends on experiences in childhood. Therefore, understanding social-emotional development can help in making more informed decisions and cultivating empathy toward others.

Example: Learning to Share

- Imagine a toddler who is playing with blocks.

- At first, the toddler may refuse to share.

- Over time, supportive caregivers might encourage sharing and model kind behavior.

- Eventually, the child learns the social benefit of sharing and feels more comfortable playing with others.

Practice Problem:

- Think of a time when a friend refused to share or cooperate.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify the behavior: refusing to share or cooperate.

- Consider the age and social experiences involved.

- Recognize that repeated guidance from parents or peers can change this behavior.

- Conclude that social-emotional development is shaped by consistent interactions and feedback.

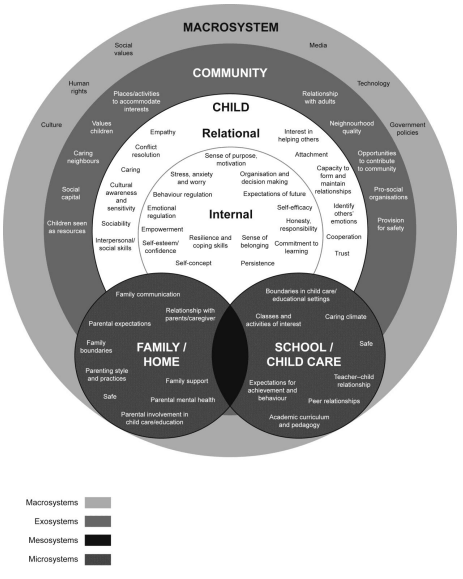

The Ecological Systems Theory

The ecological systems theory explains how our environment influences social-emotional development. According to this theory, five nested systems affect an individual:

- Microsystem: Directly affects a person (e.g., family, friends, school).

- Mesosystem: Refers to the relationships among elements in the microsystem (e.g., how parents interact with a child’s teachers).

- Exosystem: Involves external factors that indirectly affect the individual (e.g., a parent’s workplace policies).

- Macrosystem: Involves cultural or societal norms that shape behavior (e.g., values around child-rearing).

- Chronosystem: Reflects the role of time and life stages (e.g., transitions from childhood to adolescence).

Example: A Child’s Football Sessions

- A child plays on a local football team (microsystem).

- The coach speaks regularly with the child’s parents (mesosystem).

- The local sports club sets game schedules that might cause the parents to miss work (exosystem).

- Cultural attitudes toward sports participation influence how others support the team (macrosystem).

- As the child grows older, the role of the sport may change, reflecting different developmental priorities (chronosystem).

Practice Problem:

- Create a scenario where an adolescent’s grades drop because of external influences.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify the microsystem (school, family, peer group).

- Show how relationships among these groups form the mesosystem.

- Consider how a parent’s job loss (exosystem) impacts the teen’s study environment.

- Include broader cultural views on academic success (macrosystem).

- Show how the teen’s current life stage (chronosystem) interacts with these factors.

Parenting Styles and Their Cultural Implications

Parenting styles are commonly classified as authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive. Each style involves different levels of warmth, discipline, and expectations. These styles often look different across cultures because societies have varying norms about obedience, independence, and respect.

- Authoritarian: High demands with low responsiveness (strict rules, less warmth).

- Authoritative: High demands with high responsiveness (clear rules balanced with support).

- Permissive: Low demands with high responsiveness (few rules, much freedom).

These styles can influence how children form relationships across the systems. For example, an authoritative parent who sets rules but remains warm may produce a child who respects boundaries while feeling secure.

Example: How Parenting Style Influences Social Skills

- A child with authoritarian parents may feel anxious about making mistakes in social situations.

- Another child with authoritative parents may confidently ask questions and try new activities.

- A child with permissive parents might have more freedom, though they may seek structure later at school.

Practice Problem:

- Decide which parenting style might produce the most cooperative behavior in group projects.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Compare each parenting style’s structure and warmth.

- Recognize that authoritative parenting balances rules with support.

- Predict that children from authoritative families often learn teamwork and respect.

- Conclude that an authoritative style may lead to greater cooperative behavior.

Attachment Styles in Infants and Children

Attachment describes the emotional bond that infants form with caregivers. Researchers classify attachment styles as secure or insecure, with insecure subdivided into avoidant, anxious, and disorganized. A child’s temperament can also affect how easily they form secure bonds.

Separation anxiety can be a sign of strong attachment, though it may become stressful if it is extreme. Studies involving infant monkeys once demonstrated that comfort (soft maternal touch) can matter more than food in building an emotional bond, showing that food and emotion can be connected but that nurture often prevails.

Example: “Comfort over Food” from Monkey Studies

- Researchers introduced infant monkeys to two surrogate “mothers.”

- One provided food, but it was made of wire. The other offered no food but was covered in soft cloth.

- The monkeys spent more time clinging to the cloth-covered mother for comfort, despite it not offering food.

Practice Problem:

- Imagine a child who clings tightly to a caregiver during drop-off at a daycare.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Observe signs of separation anxiety.

- Explore whether the child’s reaction is linked to a secure or anxious attachment.

- Identify caregiver behaviors that can ease this transition (consistent reassurance).

- Connect the child’s temperament with the caregiver’s style to interpret the overall attachment.

Peer Relationships and Adolescence

As children grow, peer relationships become more complex. Younger children may engage in parallel play (playing side by side but not interacting) or pretend play (imagining roles and scenarios). Moving into adolescence, friendships become deeper, and approval from peers can strongly affect self-esteem.

Teenagers often experience forms of egocentrism, including the imaginary audience (believing everyone is watching them) and the personal fable (thinking their feelings are unique). These mental processes mold how adolescents view themselves and others.

Example: Peer Influence on Self-Esteem

- An adolescent joins a new sports team.

- Positive feedback from teammates boosts self-confidence.

- Any criticism may feel magnified due to the imaginary audience concept.

Practice Problem:

- Think of a situation where peer pressure changes a teenager’s behavior.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify the peer group’s stance (e.g., encouraging or discouraging a certain activity).

- Note how the adolescent’s desire for acceptance shapes choices.

- Recognize the role of egocentrism in feeling judged by peers.

- Conclude that adolescent behavior is strongly impacted by the opinions of others.

Social Development in Adulthood

Social-emotional development continues through adulthood. Culture influences when adulthood begins and what life events are considered milestones. Some cultures have an “emerging adulthood” phase, where people explore career and relationship options before settling.

Healthy adult relationships depend on mutual support and effective communication. Interestingly, the attachment style formed in childhood can affect how adults bond with romantic partners or friends.

Example: Career Choices and Early Relationships

- A young adult who grew up feeling secure tends to explore job opportunities confidently.

- In contrast, someone with anxious attachment might hesitate, fearing rejection or failure.

- Cultural differences determine the timeline and expectations for choosing a career.

Practice Problem:

- Consider an adult deciding whether to move away from family for a new job.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Assess the adult’s attachment history (secure or insecure).

- Evaluate cultural norms about independence and filial responsibility.

- Factor in the individual’s support system.

- Conclude how these elements impact the decision-making process.

Psychosocial Development Stages

Psychosocial development describes key conflicts people face during multiple life stages. These stages are a reconceptualization of the psychosexual theory, focusing on social conflicts rather than only biological drives. Each stage presents a challenge that can result in growth or difficulty:

- Trust vs. Mistrust

- Autonomy vs. Shame/Doubt

- Initiative vs. Guilt

- Industry vs. Inferiority

- Identity vs. Role Confusion

- Intimacy vs. Isolation

- Generativity vs. Stagnation

- Integrity vs. Despair

Each conflict has unique effects on social development and mental processes.

Example: Real-Life Scenarios

- A baby who receives consistent care develops trust (Trust vs. Mistrust).

- A teen exploring different groups may struggle with Identity vs. Role Confusion.

- An older adult looking back on life may face Integrity vs. Despair.

Practice Problem:

- Identify which stage involves developing a sense of purpose through social roles.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Recognize that each stage has a specific task.

- Recall that Initiative vs. Guilt (Stage 3) focuses on exploring abilities and asserting power.

- Conclude that a sense of purpose emerges here before major social roles in later stages.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Social Development

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include events like abuse, neglect, or family dysfunction. These experiences can influence social relationships and mental processes in adulthood. Moreover, cultural interpretations of what is considered an ACE vary.

Example: Cultural Responses to ACEs

- In one culture, loss of a caregiver may lead to extensive community support.

- In another, stigma surrounding trauma may limit resources for healing.

- These differences affect how the individual recovers and forms healthy adult relationships.

Practice Problem:

- Compare how two different cultures might respond to a child who grows up with prolonged stress.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify the ACE (e.g., witnessing conflict at home).

- Describe Community A’s supportive approach (group counseling, traditions of care).

- Contrast with Community B’s possible reluctance to discuss mental health.

- Conclude that sociocultural factors shape the child’s path to recovery.

Identity Development in Adolescents

Identity formation happens through the processes of achievement, diffusion, foreclosure, and moratorium. Adolescents may explore various identities (racial, ethnic, gender, sexual orientation) while imagining possible selves.

Example: Shaping an Identity Through Experience

- A high school student tries different extracurricular clubs (moratorium).

- Another student sticks to a predetermined career path suggested by parents (foreclosure).

- Reaching an achievement involves exploring and committing to a clear identity.

Practice Problem:

- Think of a teenager who experiences confusion about career goals.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Recognize the confusion as identity diffusion if there is no commitment.

- Identify whether the teen is experimenting or just feeling lost (moratorium vs. diffusion).

- Suggest exploring options systematically (volunteering, talking to mentors).

- Conclude that open exploration can lead to identity achievement over time.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a summary of key concepts related to social-emotional development.

| Term/Concept | Definition or Key Feature |

| Ecological Systems | Five systems (micro-, meso-, exo-, macro-, chrono-) affecting development |

| Parenting Styles | Authoritarian, Authoritative, Permissive; vary by warmth and control |

| Attachment Styles | Secure, Insecure (avoidant, anxious, disorganized); influenced by caregiver responsiveness |

| Separation Anxiety | Heightened anxiety/fear in infants when away from caregivers |

| Peer Relationships | Develop via parallel and pretend play in childhood; peer approval gains importance in adolescence |

| Egocentrism (Teens) | Imaginary audience (feeling watched) and personal fable (unique experiences) |

| Emerging Adulthood | Transitional period with exploration in career, personal goals |

| Psychosocial Stages | Eight conflicts from Trust vs. Mistrust to Integrity vs. Despair |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | Traumatic or stressful events in childhood that may impact adult well-being |

| Identity Formation | Processes: Achievement, Diffusion, Foreclosure, Moratorium |

Conclusion

Social-emotional development is a lifelong journey shaped by relationships, cultural differences, and life stages. By exploring the ecological systems theory, parenting styles, attachment concepts, peer dynamics, and psychosocial challenges, insight is gained into how people grow and adapt over time.

Studying concepts such as separation anxiety, food and emotion, and the psychosocial theory sheds light on how behavior and mental processes change with each phase of life. Finally, recognizing the effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and identity formation helps demonstrate the importance of supportive environments. Developing a deeper understanding of social-emotional development offers valuable perspectives for fostering empathy, communicating effectively, and guiding growth in oneself and others.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Psychology

Are you preparing for the AP® Psychology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Psychology problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- Language and Communication: AP® Psychology Review

- What is Operant Conditioning: AP® Psychology Review

- Learning Theory: AP® Psychology Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Psychology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Psychology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.