What We Review

Operant conditioning is a method of learning that uses rewards and punishments to shape behavior. This approach is closely tied to how people develop habits, overcome challenges, and respond to various situations. Therefore, understanding operant conditioning and behavior can help explain daily interactions, such as why a friend might offer praise to encourage a good habit or why a teacher might correct a student’s mistake to discourage an unwanted behavior.

Psychologist B.F. Skinner popularized this concept through research on how consequences influence future actions. His findings led to insights about how behaviors are repeated or eliminated, depending on the outcomes they produce.

What Is Operant Conditioning?

Operant conditioning is a type of learning in which a subject’s behavior becomes more or less likely to happen again based on the consequences that follow it. In everyday terms, if doing something leads to a pleasant consequence, that action tends to increase over time. Conversely, if doing something leads to an unpleasant outcome, it is less likely to happen in the future.

Historically, B.F. Skinner advanced the field by studying how rewards and punishments affect animals. He built on the findings of Edward Thorndike, who observed that behaviors followed by favorable results often reoccurred, whereas those followed by undesirable results gradually disappeared.

Example: Working on Chores

Scenario: Imagine a teenager who decides to wash the dishes without being asked.

- Step 1: The teenager’s parent notices this helpful action.

- Step 2: The parent expresses gratitude or gives an allowance.

- Step 3: The teenager is more likely to continue washing dishes in the future because the behavior led to a positive outcome.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Identify a routine task (such as tidying up a desk).

- Notice any reward or punishment offered after completing the task.

- Evaluate how the presence or absence of a reward or punishment affects the desire to repeat or avoid the task.

The Law of Effect

The Law of Effect states that when a behavior has a satisfying result, it is more likely to happen again. However, if the result is unsatisfying, the behavior is less likely to be repeated. Therefore, this principle underlies operant conditioning by emphasizing outcomes.

Example: A Student Studying for Exams

Scenario: A student decides to study for more hours each evening.

- Step 1: The student notices they begin to score higher on quizzes.

- Step 2: The improved grades feel rewarding and encourage more study sessions.

- Step 3: Over time, the student forms a habit of studying because the positive consequence reinforces the behavior.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Think of a personal goal (for instance, completing homework on time).

- Track each time the behavior leads to a success or a mistake.

- Determine whether each outcome encourages or discourages a repeat of that behavior in the future.

Reinforcement and Punishment

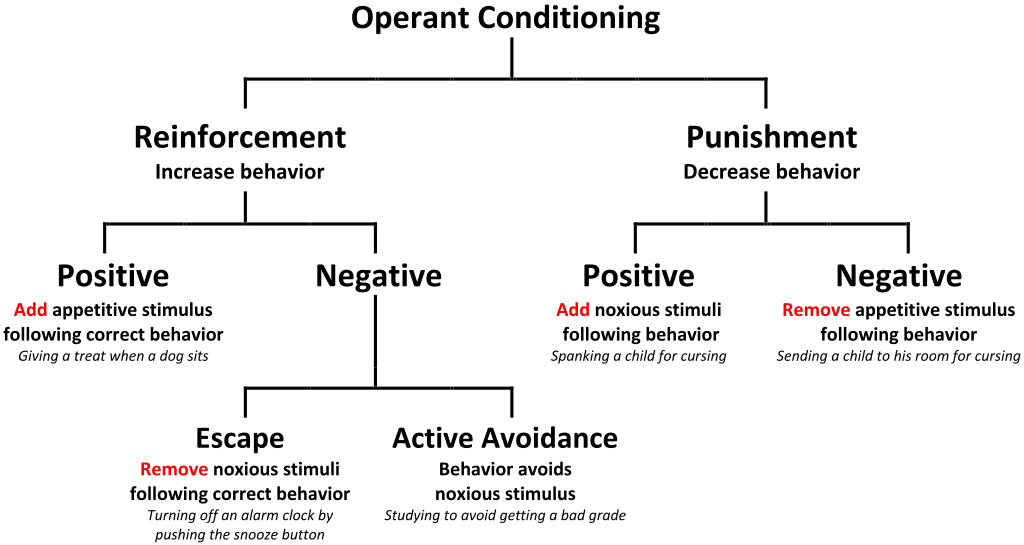

Reinforcement makes a behavior more likely to recur, while punishment makes a behavior less likely to continue. These categories break down into four main variables of operant conditioning:

- Positive Reinforcement: Adding a pleasant stimulus after a behavior (e.g., giving praise).

- Negative Reinforcement: Removing an unpleasant stimulus after a behavior (e.g., turning off a loud alarm).

- Positive Punishment: Adding an unpleasant stimulus to discourage a behavior (e.g., scolding).

- Negative Punishment: Taking away a pleasant stimulus to discourage a behavior (e.g., losing privileges).

Example: Training a Dog to Sit

Scenario: A dog owner wants the dog to sit on command.

- Step 1: The dog owner holds a small treat.

- Step 2: When the dog sits, the owner immediately offers praise and a treat (positive reinforcement).

- Step 3: Over time, the dog associates the act of sitting with the reward and is more likely to obey.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Pick a simple behavior to encourage, such as greeting someone politely.

- Decide on a suitable reward (positive reinforcement) or removal of something unpleasant (negative reinforcement).

- Apply the chosen reinforcement each time the desired behavior occurs.

- Observe how often the behavior is repeated.

Types of Reinforcers

Reinforcers can be primary or secondary.

- Primary Reinforcers: These satisfy basic biological needs, such as food, water, or warmth.

- Secondary Reinforcers: These have no inherent value unless combined with primary reinforcers. Money, praise, and stickers are examples because they gain value through learned associations.

Example: Using Food as a Primary Reinforcer

Scenario: An animal trainer gives small pieces of food to a dolphin during a routine.

- Step 1: Each time the dolphin performs a trick correctly, it receives fish (primary reinforcer).

- Step 2: Over time, the trainer may pair a whistle sound (secondary reinforcer) with the fish.

- Step 3: Eventually, the whistle alone can signal success and reinforce the behavior, even before the fish is delivered.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Choose a desired behavior, such as helping classmates.

- Provide a direct reward (like a compliment or star sticker).

- If the reward works consistently, you have discovered a potential secondary reinforcer.

Shaping Behavior

Shaping is the process of gradually guiding an organism toward a desired behavior by reinforcing closer and closer approximations of it. Instead of waiting for the final action to appear, small steps are rewarded along the way.

Example: Teaching a Child to Ride a Bicycle

Scenario: A child is learning to balance and pedal.

- Step 1: At first, give praise when the child simply sits on the bike (first approximation).

- Step 2: Next, reward the child for pedaling even if only for a few seconds.

- Step 3: Over time, the child can ride the bike with complete balance, reinforced for mastering each stage.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Choose a skill or habit (such as learning basic guitar chords).

- Break the skill down into small milestones (e.g., strumming a chord correctly, then switching chords, then playing a short melody).

- Offer reinforcement at each milestone so that the learner stays motivated.

Superstitious Behavior and Learned Helplessness

Sometimes, behaviors can be repeated even when the result is not truly related. This is called superstitious behavior. Athletes, for example, might wear the same socks for every game, believing it helps them win.

By contrast, learned helplessness occurs when individuals come to believe they have no control over unpleasant situations. If repeated failures occur, they may give up, even if a solution becomes available later.

Example: A Student Who Gives Up After One Failed Test

Scenario: A student studies but fails a test anyway.

- Step 1: The student feels the outcome is uncontrollable.

- Step 2: The student stops trying for future tests, believing no effort will help.

- Step 3: As a result, grades continue to drop due to a lack of further study.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Reflect on a personal disappointment (such as losing a competition).

- Notice any beliefs about not having control.

- Identify realistic steps or techniques that could correct or improve the situation.

- Practice applying these steps to break the cycle of learned helplessness.

Reinforcement Schedules

Reinforcement schedules define how often and under what conditions reinforcement is given. They are usually divided into two categories:

- Continuous Reinforcement: A reward is given every time the desired behavior is performed.

- Partial Reinforcement: A reward is given only some of the time.

Under partial reinforcement, four main schedules exist:

- Fixed Ratio (FR): Reinforcement after a set number of responses (e.g., every 5th correct response).

- Variable Ratio (VR): Reinforcement after a random number of responses (e.g., a slot machine).

- Fixed Interval (FI): Reinforcement after a set time period (e.g., every two weeks).

- Variable Interval (VI): Reinforcement after an unpredictable time period (e.g., a random pop quiz).

Example: Training a Pet With a Continuous vs. Variable Ratio Schedule

Scenario: A person wants to teach a pet bird to whistle a tune.

Continuous Schedule (Step-by-Step):

- Each time the bird makes a sound close to the target tune, it gets a treat.

- The bird quickly learns to imitate the tune because the reward is reliable.

Variable Ratio Schedule (Step-by-Step):

- The bird only gets a treat sometimes when it whistles the tune.

- The bird continues to whistle more often, hoping each time will be rewarded. This can lead to a higher rate of the behavior.

Practice Activity (Step-by-Step):

- Select a simple behavior to reinforce (e.g., completing a math problem).

- First, apply continuous reinforcement for a few trials.

- Switch to a partial schedule (like a fixed ratio).

- Observe how the behavior changes when the reinforcement becomes less predictable.

Conclusion

Operant conditioning is central to behavior modification. By understanding the Law of Effect, as well as different forms of reinforcement and punishment, it becomes easier to see how everyday actions are shaped. Furthermore, knowing about schedules of reinforcement, superstitions, and learned helplessness can guide more effective habits and problem-solving strategies. Therefore, students and teachers can use these principles to create positive learning environments and foster success in daily life.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a quick guide to key terms in operant conditioning:

| Term | Definition |

| Operant Conditioning | A type of learning in which behaviors are influenced by consequences (rewards or punishments). |

| Law of Effect | Behaviors followed by positive outcomes are more likely to recur, while those followed by negative outcomes are less likely to recur. |

| Positive Reinforcement | Adding a pleasant stimulus to increase a behavior (e.g., giving a treat). |

| Negative Reinforcement | Removing an unpleasant stimulus to increase a behavior (e.g., turning off a loud noise). |

| Positive Punishment | Adding an unpleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior (e.g., giving extra chores). |

| Negative Punishment | Removing a pleasant stimulus to decrease a behavior (e.g., taking away video game time). |

| Primary Reinforcer | Something inherently satisfying or desirable (e.g., food, water). |

| Secondary Reinforcer | Something that gains its reinforcing power through association (e.g., money or tokens). |

| Shaping | Gradually reinforcing successive steps toward the desired behavior. |

| Superstitious Behavior | When a behavior is accidentally reinforced, leading someone to believe that unrelated actions cause specific outcomes. |

| Learned Helplessness | When individuals learn they have no control over negative experiences, causing them to stop trying altogether. |

| Continuous Reinforcement | Reward given every time the desired behavior occurs. |

| Partial Reinforcement | Reward given only some of the time, which includes fixed/variable interval and fixed/variable ratio schedules. |

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Psychology

Are you preparing for the AP® Psychology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Psychology problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- What is Cognitive Development: AP® Psychology Review

- Language and Communication: AP® Psychology Review

- Social Emotional Development: AP® Psychology Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Psychology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Psychology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.