What We Review

Intelligence and academic achievement are core concepts in psychology that help explain how individuals learn and perform in various settings. Understanding how psychologists define intelligence in psychology and measure it provides valuable insights into the human mind. Moreover, recognizing the difference between intelligence tests and achievement tests helps clarify why scores in these areas do not always match. Therefore, this article offers an overview of intelligence definitions, measurements, and historical shifts while also highlighting how academic achievement is measured. By reviewing these topics, high school students can develop a better grasp of intelligence theory and its practical implications.

Defining Intelligence in Psychology

Psychologists have long debated how to define intelligence. Early views focused on a single general ability, often called “g.” However, more recent work suggests multiple intelligences. Howard Gardner’s theory proposes abilities such as logical-mathematical intelligence, linguistic intelligence, and interpersonal intelligence as separate yet valuable forms of intellect. Researchers continue to discuss whether these intelligences exist independently or form part of a unified construct.

Example: Traditional vs. Multiple Intelligences

Imagine two students. The first excels in math tests, while the second is an outstanding pianist and works well with others. Some might view intelligence in terms of test performance, emphasizing the first student’s abilities. However, Gardner’s framework would also acknowledge the second student’s musical and interpersonal strengths as equally important.

Step-by-Step Analysis:

- Identify the type of intelligence being displayed (e.g., musical, logical, or interpersonal).

- Compare that intelligence to a single-test view (traditional IQ approach).

- See how recognizing multiple intelligences can broaden understanding of individual talents.

How Intelligence Is Measured

Researchers have devised various tests to capture “intelligence” in a single score or set of scores. Early tests led to the idea of an Intelligence Quotient, or IQ. This original calculation divided a person’s mental age by chronological age, then multiplied by 100. Modern IQ testing involves standardized procedures designed to ensure everyone takes the test in similar conditions. Well-known IQ tests often include sections on verbal comprehension, working memory, and processing speed.

Key Considerations

- Standardization: A test must be administered in consistent settings for fairness.

- Validity: Tests need to measure what they claim to measure. Construct and predictive validity ensure accurate evaluations and forecasts of future performance.

- Reliability: Tests should yield consistent results over multiple administrations. Examples include test-retest reliability and split-half reliability.

Example: Calculating an IQ Score

Early intelligence tests relied on a simple formula. Assume a child with a mental age of 8 years old and a chronological age of 6 years old. The original IQ calculation would be: \text{IQ} = \frac{\text{Mental Age}}{\text{Chronological Age}} \times 100

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Identify mental age (8 years) and chronological age (6 years).

- Divide: \frac{8}{6} = 1.33 (approximately).

- Multiply by 100: 1.33 \times 100 = 133.

- Conclude that the child’s IQ, by this classic method, would be 133.

Changes in Intelligence Testing

Historically, intelligence tests targeted specific groups. Over time, biases emerged that affected test results, especially among individuals from varied cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Therefore, modern efforts focus on socio-culturally responsive assessments, trying to minimize stereotype threats and bias.

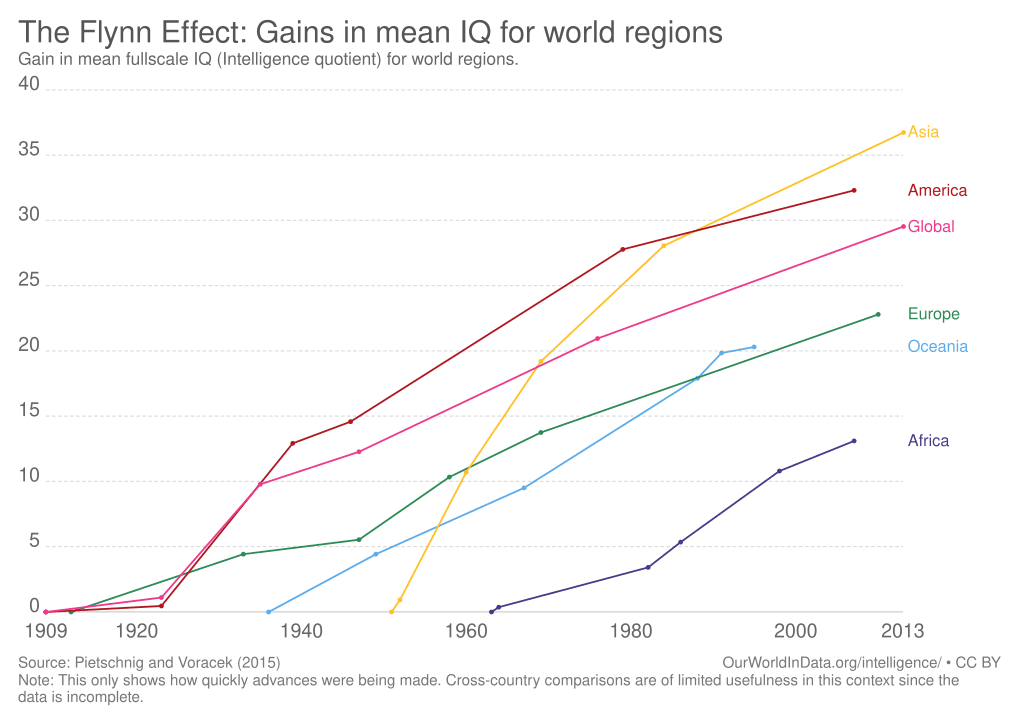

A noticeable trend called the Flynn Effect reveals that IQ scores have generally risen over the past decades. Researchers believe improvements in nutrition, health care, and education have played critical roles. This effect highlights how intelligence testing is not just about innate ability but is also influenced by environmental factors.

Example: Flynn Effect in Action

Imagine that a student’s grandmother took an IQ test in 1960 and scored 100, which was average at that time. Now, the same raw score might register closer to 90 in a current population because overall performance levels have shifted upward.

Step-by-Step Explanation:

- Recognize that average IQ scores remain around 100 due to periodic re-norming.

- Realize that raw test performance has increased, so a 1960 score of 100 may no longer match today’s test norms.

- Understand this shift as evidence of improved factors like schooling and nutrition.

Systemic Issues Affecting Intelligence Assessments

Socioeconomic status, health, education, and cultural understanding significantly impact test performance. When individuals lack fair access to high-quality education or good nutrition, IQ scores can suffer. Discrimination may also widen opportunity gaps.

Therefore, intelligence measurements alone may not reflect the full potential of an individual when other factors limit performance. Additionally, researchers emphasize that greater differences in IQ exist within groups than between them. Thus, broad assumptions about entire populations can be misleading and may lead to unfair policies.

Example: The Impact of Poverty

Consider a young child who lives in an under-resourced neighborhood and attends a school with limited materials. The child’s test scores may be lower, not because of innate limitations but due to restricted educational opportunities.

Step-by-Step Insight:

- Examine the child’s living conditions (poor nutrition, lack of educational resources).

- Note how these conditions make it difficult to perform as well on standardized measures.

- Conclude that intelligence may be underestimated when systemic barriers exist.

Academic Achievement vs. Intelligence

While intelligence tests gauge reasoning and problem-solving skills, academic achievement tests measure what someone knows or can do in specific subjects. Achievement tests, like end-of-course exams, focus on how well students have mastered the material. Aptitude tests, in contrast, try to predict future performance in certain ability areas.

Moreover, research shows that beliefs about intelligence can influence student performance. Those who view intelligence as fixed from birth may not strive to improve as much, while those with a growth mindset—who believe intelligence can be developed—tend to put in more effort.

Example: Achievement Test Scenario

Picture a student taking an advanced math test at the end of the year. This test measures the student’s mastery of algebraic concepts rather than overall reasoning ability.

Step-by-Step Explanation:

- Identify the subject focus (algebra).

- Note that the purpose is to measure knowledge learned over the year.

- Compare these results to an IQ test that measures broader cognitive skills, not specific algebra concepts.

Conclusion

Psychologists continue to refine how intelligence is defined and assessed. At the same time, academic achievement reflects knowledge in specific domains. Therefore, it is helpful to keep in mind that test results are shaped by standardization, validity, reliability, and environmental factors. By examining the connections between intelligence and achievement, students gain insight into how test scores can guide, but not fully determine, success. Further exploration of these themes encourages a deeper understanding of human potential and the variety of factors that contribute to learning.

Quick Reference Chart

Below is a quick reference table of key terms and definitions related to intelligence and academic achievement.

| Term | Definition |

| Intelligence | A broad construct involving mental abilities such as reasoning, problem-solving, and learning. |

| General Intelligence (g) | The idea that intelligence reflects a single underlying factor influencing an individual’s cognitive abilities. |

| Multiple Intelligences | A theory suggesting that intelligence can be divided into distinct areas, like musical, logical, or interpersonal. |

| IQ (Intelligence Quotient) | A numerical score initially calculated as \frac{\text{mental age}}{\text{chronological age}} \times 100. |

| Standardization | Ensuring that testing conditions and procedures are consistent for all participants. |

| Validity | The degree to which a test measures what it claims to measure (e.g., construct or predictive validity). |

| Reliability | The consistency of a test’s results across multiple administrations or different halves of the test. |

| Flynn Effect | The observed rise in average IQ scores over time, often attributed to better nutrition, education, and health care. |

| Stereotype Threat | The risk of confirming a negative stereotype about one’s group, which can affect performance on tests. |

| Academic Achievement | Performance in specific subject areas, generally measured through exams and graded coursework. |

| Achievement Tests | Instruments that measure how much a person has learned in a given subject or skill. |

| Mindset | A set of beliefs about the malleability of intelligence (fixed vs. growth mindset). |

Remember these terms to get a solid grasp of how intelligence is measured, how intelligence tests have changed, and how academic achievement differs from IQ testing. Considering IQ limitations and potential biases is essential for interpreting test results fairly.

Sharpen Your Skills for AP® Psychology

Are you preparing for the AP® Psychology test? We’ve got you covered! Try our review articles designed to help you confidently tackle real-world AP® Psychology problems. You’ll find everything you need to succeed, from quick tips to detailed strategies. Start exploring now!

- Forgetting: AP® Psychology Review

- Memory Retrieval: AP® Psychology Review

- Types of Thinking in Psychology: AP® Psychology Review

Need help preparing for your AP® Psychology exam?

Albert has hundreds of AP® Psychology practice questions, free response, and full-length practice tests to try out.